|

Claws/Hooves Development & Induction

Normal Development:

So much of development is due to epithelial-mesenchymal

interactions, where almost always the mesenchyme

provides the initial signal that induces the responding

tissue, the epithelial. Hoof and claw development is a

perfect example; they are formed because of a series of

reciprocal exchanges of inductive signals. In the case

of limb development it is the somatic mesoderm that is

responsible for the initial signal to the limb dermis.

There is a limb morphogenic field that is committed to

give rise to the limb and will do so upon receiving the

right induction signal. Tbx4 is a transcription factor

that is expressed in the hind limbs and in combination

with a growth factor, FGF, the limb out grows and forms

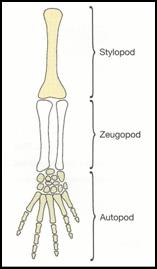

the hooves. As the limb grows outward, the stylopod

forms first, followed by the zeugopod and then the

autopod; this shows how the tissues are differentiated

in the proximal to distal order. Each phase of limb

development requires a particular expression of hox

genes. BMPs are expressed in the distal area of the

sclerotome and BMPs both induce apoptosis to form the

digits but also help differentiate mesenchyme cells into

cartilage. In normal development BMPs are inhibited so

that apoptosis can take place and digits and joints are

formed. Claws form similar in which a claw field

develops as an epithelial thickening on the dorsal side

of each digit. This epithelial thickening, or placode,

is the first sign of induction for an epithelial

appendage. Next to this placode a transverse groove

appears and forms a deep fold in the epidermal matrix

and the cells of this matrix produce a keratinized layer

that slides distally over the claw bed. (Hamrick 2001).

© 1999 by John Stear

(Click on Image to view Original Source)

How we differ:

Although much of our development appears to be very

similar to this so-called chick creature, we do differ

in some of the hooves and claw development. It appears

that our development is very similar for the stylopod

and zeugopod, but differs at the autopod region.

Whereas the chick embryo secretes noggin, a BMP

inhibitor, it is obvious that we lack this factor

because it is the increase expression of BPM that

converts the mesechyme of the digits to cartilage which

will later form hard keratin and form the hooves

(Gilbert 2003). Our specific claw pattern develops

through interactions with SHH which is expressed in the

region of the limb bud called the zone of polarizing

activity (ZPA), which is a region

of mesoderm located between the limb bud and the body

wall which affects the development of digits in the

limb. SHH induces a signal that affects the surrounding

hox genes and this epithelial-mesenchyme interaction is

what results in the claws of the hooves. We seem

to display a Hoxd-13 mutation, (as those people on earth

call it) which is why the claws on its hooves can fuse

together. Thereby, three claws form instead of the

normal five found in most vertebrates on earth. In

creatures on earth, this is considered a deformity known

as syndactyly, as seen below. This syndrome is

analogous to the our normal claw.

© 2005 by Jon A. Baskin

(Click on Image to view Original Source)

© 2005 Florida Museum of Natural History

© 1996-2003 Nesssus

(Click on Image to view Original Source)

(Click on Image to view Original Source)

The central digit becomes increasingly stronger while

the “side digits” become less important and are

virtually lost in us.

Sources:

Gilbert, Scott F. Development Biology. 7th

Editon. Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc., 2003.

Hamrick, Mark W. “Development and evolution of the

mammalian limb: adaptive diversification of nails,

hooves, and claws.” Evolution and Development. Volume 3,

Issue 5, Page 355. September-October 2001.

Tosney, K. Lecture Material. Bio 208, Fall 2004

|