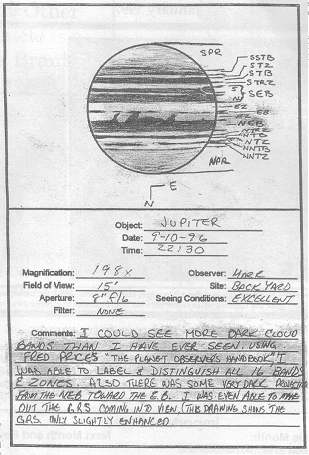

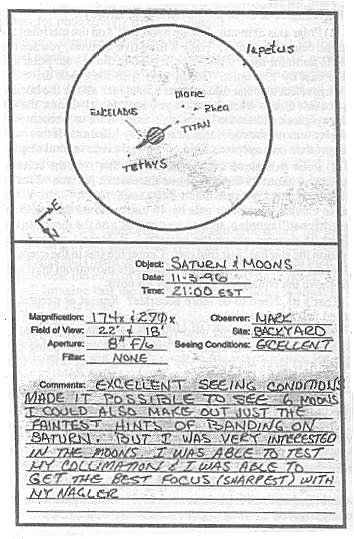

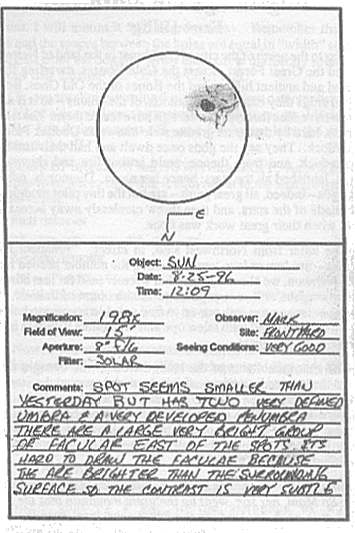

I have been sketching my observations at the telescope for almost as long as I have been observing - which, by the way, has only been about two years. In this time I’ve made about 85 drawings, of planets, globular and open clusters, planetary, diffuse and reflection nebulae, galaxies, double stars, comets, and sunspots. My earliest drawings are a bit on the crude side and lack detail, but they are still a good representation of just what can be seen through the eyepiece of my scope (a Meade 8” f/6 Newtonian on a simple Dobsonian alt-az mount).

The reason for the title of this article is simple: I’ve noticed that as I try to sketch what I see in a given field of view (FOV), I begin to notice more details that I’d originally missed. Because my telescope doesn’t track the sky, I have to gather as much as I can during the time it takes an object to drift across the FOV - and as most of you know, the rule is that the higher the magnification, the smaller the FOV. So I have developed a number of helpful sketching techniques that have resulted in an overall improvement in my general observing skills, and in an off-hand way improved my eyes (or perhaps my brain) in their ability to pick out fine detail quickly.

Here are some of the tips and techniques I’ve learned while sketching what I see through the eyepiece:

OK, if you’ve read all the advice above, you’re ready to start drawing! (Well, OK, you do have to wait until the clouds move on....) It takes some restraint to keep from putting in details that you really haven’t seen outside of photographs; but as you work on drawing what you see you’ll probably find that you’re noticing details that you’d missed on the first glance. I like to position an object just off the eastern edge of the FOV and let it drift into view - this gives me the most time to study the object and decide which features are the most significant. It’s these outstanding features that I draw first; detail in the drawing is not as important as position and size at this point, so look to see the shape and how it relates to the stars in the FOV. Stars are drawn as dots, with their brightness indicated by the size and darkness of the spot (remember that by drawing with a black pencil on white paper you’re creating a negative of what you’re actually seeing - the brighter a feature is, the darker it appears in the drawing).

Once you’ve got the background stars and basic shape, go back for another long look to pull out more subtle details - changes in the brightness, faint wisps of nebulosity, dark lanes or festoons. You can use your fingertip or an eraser to smudge features that you’ve drawn too clearly - but study the object for as long as you can, let it drift all the way across the FOV, and you’ll be amazed at how much detail you really can see! There may be moments when the turbulence dies down completely for a few seconds, and the view will become crystal clear and filled with fine detail; but these moments may come only every five or ten minutes. Patience really is a virtue for this job!

Don’t worry too much if your first few attempts won’t make it to the walls of a “highbrow” art gallery; remember that most amateurs are “lowbrow” just like us. If you want to start with something fairly easy, why not work on double stars? Chris Sarnecki has sketched dozens of them, and he’s found that they don’t need to be works of art to be accurate representations of what he’s seen through his scope. I was recently surfing the web and found a site that has the entire Messier catalog in hand-drawn form.

[The web site Mark is refering to (Larry’s Deep-Sky Sketches) can be found at http://home.comcast.net/~lsmch/Sketch1.htm.]

So get out and try it! Trust me, the more you sketch, the better you’ll get - and the more you’ll see!

[The Lowbrow web site contains some additional sketches by Mark, including some of Jupiter, one of Mars and one of the comet Hale-Bopp.]