Well, it happened again. Remember Gracie and her bear, about whom I wrote a few months back? Check out the August 2010 edition of Reflections if you missed it [see Doug Scobel. “Gracie’s Bear.” August, 2010]. In the article I relate an encounter with an apparent amateur-astronomer-to-be while observing up north. Well, it happened again at our last open house (you know, the one where Mark [Low]brow-beat us into attending). This time the encounter was with a remarkable third-grader named Allison.

Jupiter and two of Jupiter’s moons, Io and Ganymede.

Do you remember November 6? If Mark’s cajoling didn’t, then the cloudless, pure azure late afternoon skies surely convinced many of us into attending what could have been our last open house of the year, yours truly included. It looked like it was going to be one of those perfect nights. But alas, around sunset, a last-minute cloud bank made its appearance and never totally relinquished its grip on the skies over Peach Mountain. A group of cub scouts made their presence known early, but the clouds, while thin, didn’t afford us any targets for the boys and their families. It didn’t take long for them to get tired of waiting and they ended up leaving. Too bad they left when they did, because it wasn’t long after that when the cloud bank started to thin and a few objects started to become visible. The first was Jupiter, and it wasn’t long before most scopes were pointed in his direction. About that time a group of several families arrived. The first scope in line from the pavement was Mark’s big and beautiful Blondie, but when I saw the number of people lining up at his scope I suggested that some could come look through mine as well. By now Jupiter was winking in and out, in concert with the small gaps between the clouds as they slowly passed overhead. I had to encourage our guests to stay at the eyepiece for a while lest they miss a gap in the clouds where Jupiter would look really good. There were a few boys, their apparent parents, and one young girl taking turns at the eyepiece. Now this girl was a little different in how she approached her viewing. Most of the others would take a quick look and say “Cool”, and then move on to another scope. But she actually took her time. She was actively studying what she was seeing, not just looking.

I would ask “Do you see the bands across the planet?” “Yes I do” she said. “Those are Jupiter’s clouds. Do you see those bright stars to the right of the planet? Those are some of Jupiter’s moons”. “Yes, I see them” she replied while still glued to the eyepiece. Then came the unexpected. Some questions. Really serious questions. Not how far away is it, or how big is it, but more along the lines “What are the clouds made of? Do the moons ever crash into each other?” Not an unreasonable question, since they’re all in a row and, hmmm, maybe they could run into each other. So I tried to explain to a young child the clouds are made of methane and other gasses, and how each moon is in its own circle going around the planet, and they stay in their circles so they never run into each other. She nodded as if she understood — whether she truly did understand I don’t know. But while she nodded I could see the gears going inside her head, so she was definitely listening and processing and internalizing to the best of her ability.

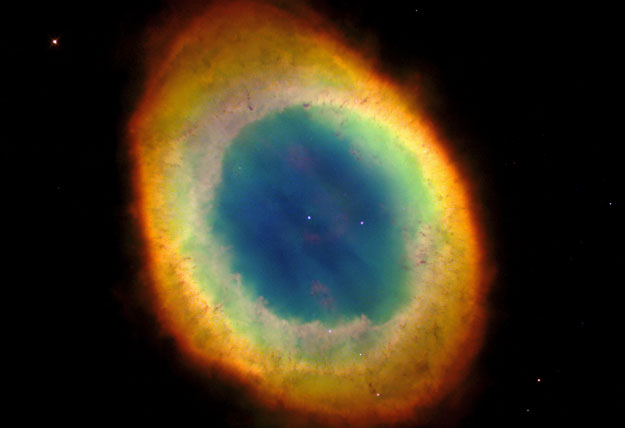

M57, The Ring Nebula.

By now the clouds were thinning more and more, with the gaps becoming larger and larger, so there were more targets available to our scopes. Soon Lyra was smack in the middle of a large open area, so naturally I went to M57, the Ring Nebula. A number of folks took turns looking, with the usual reactions, some saying “Wow!” while others I had to ask if they saw it. It wasn’t long before that same girl was at the eyepiece. “Do you see the smoke ring?” “Oh, yes, I see it.” I was pleased, because sometimes it can be a challenge for kids that age to make out the fainter, fuzzier objects. But what came next caught me off guard. “It kind of looks like a planet.” “Say what?” I thought to myself. “It kind of looks like Jupiter” she added. How astute. I told her how these kind of objects are called “planetary” nebulas because they, well, resemble planets. I then complimented her on her observing skills, and she nodded in appreciation. But she wasn’t done yet. “It’s darker on top”. She was obviously noticing that the ring isn’t equally bright all the way around. So of course I had to compliment her again. Again I received the same nod and a very polite “Thank you” in return. We looked at a few other targets, like the E.T. cluster, the Double Cluster, and others, before the clouds closed in for the night. The same girl never strayed far, and always took her time at the eyepiece, and always came up with some really good questions. And I always got that same knowing nod in reply to my attempts at answering them the best I could, and the same polite “Thank you” every time.

Once the clouds dictated that we were done with observing, I spent some time in conversation with her parents and her. I found out that her name is Allison, and she’s in the third grade. I also found out that the family owns a telescope, I think an Orion Starblast. She said that she has a “lot of questions”, so she has a natural curiosity about astronomy that doesn’t come along very often. We discussed various books that are good for beginners, I recommended “365 Starry Nights” because that was the only one I could think of off the top of my head. [Perhaps if one of her family members reads this they can go to our beginner’s book list at http://www.umich.edu/~lowbrows/biblio/youth.html]

I complimented her again, telling her what a good observer she was. And I meant it. Very few novices notice much if any of the subtle details in the things we show them, but not this little girl. She’s got the eye of the observer, and as many of you reading this know, it’s not just the eye. Just as it was with Gracie a few months earlier, she was engaging her mind, processing what she was perceiving with her senses, in this case sight, to form an understanding of something beyond her immediate self. Not that common in most of our guests, but even more remarkable considering she’s only a third grader. Very remarkable indeed. I sure hope she and her family make it out to Peach Mountain again.

My current work and volunteering schedule limits my ability to get to open houses, but you can bet that I will make a more concerted effort to do so. I don’t want to miss out on meeting another Allison. You never know when you might encounter another youngster that has the eye of the observer.

About the Jupiter Photo:

This photo appears on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (California Institute of Technology) Photojournal: http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA14410

Original Caption Released with Image: Ground-based astronomers will be playing a vital role in NASA’s Juno mission. Because Jupiter has such a dynamic atmosphere, images from the amateur astronomy community are needed to help the JunoCam instrument team predict what features will be visible when the camera’s images are taken. This image was acquired by Damian Peach on September 12, 2010, when Jupiter was close to opposition. South is up and the “Great Red Spot” is visible. Two of Jupiter’s moons, Io and Ganymede, can also be seen in this image.

Image Credit: NASA/Damian Peach, Amateur Astonomer. Image Addition Date: 2011-08-03

About the M57, Ring Nebula Photo:

This photo appears on NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day: http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap010729.html

Credit: H. Bond et al., Hubble Heritage Team (STScI /AURA), NASA

Explanation: Except for the rings of Saturn, the Ring Nebula (M57) is probably the most famous celestial band. This planetary nebula’s simple, graceful appearance is thought to be due to perspective—our view from planet Earth looking straight into what is actually a barrel-shaped cloud of gas shrugged off by a dying central star. Astronomers of the Hubble Heritage Project produced this strikingly sharp image from Hubble Space Telescope observations using natural appearing colors to indicate the temperature of the stellar gas shroud. Hot blue gas near the energizing central star gives way to progressively cooler green and yellow gas at greater distances with the coolest red gas along the outer boundary. Dark, elongated structures can also be seen near the nebula’s edge. The Ring Nebula is about one light-year across and 2,000 light-years away in the northern constellation Lyra.