Now that summer is here, planetary observing is on the downswing. Saturn is now lost in the sun’s glare, and Jupiter, long past opposition, is quickly heading for the same fate. Mars won’t be well placed for evening observing until fall. Yes, Venus is in the evening sky now, but it sets early. So what’s a planetary observer to do? Why, observe the outer planets, of course! Frequently neglected, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto are well placed in the night sky this summer, and can provide a nice diversion from deep sky observing.

Now you’re probably thinking to yourself “Been there, done that. They’re small, featureless, and unimpressive. And Pluto - forget it!” But the outer planets reveal their own brand of uniquely challenging yet rewarding visual delights to those who make the effort to seek them out.

Uranus is the next most distant planet after Saturn. Like its big brothers Jupiter and Saturn, it also is a so-called gas giant, with an equatorial diameter just under half that of Saturn. But because it lies about twice as far away as the ringed world, it presents a disk not even four seconds of arc across at its best. Despite its small angular size and great distance, it still gets up to naked eye (under dark skies) brightness, about magnitude 5.7 around opposition.

Virtually any good backyard telescope under reasonably steady skies will let you discern its small greenish-blue disk, revealing it as a planet, not a star. But don’t expect to see any detail, although some claim to see some minor albedo variations in very large telescopes under ideal viewing conditions. What is of greater interest to the visual observer is its moons. Uranus has five medium-sized moons and more than 20 smaller ones. Its two brightest moons, Oberon and Titania, at magnitudes 14.2 and 14.0, respectively, are within the grasp of many amateur-sized telescopes. Two more of its large moons, Ariel and Umbriel, at magnitudes 14.4 and 15.1, respectively, are a little more difficult to spot, partly because they are fainter, and partly because they orbit closer to Uranus than Oberon and Titania. Miranda is a distant fifth brightness-wise, at visual magnitude 16.6, so you will need a lot of aperture to glimpse it. The rest of the moons are extremely small and faint, and virtually unreachable visually.

To identify them, you’ll need a diagram showing their positions for the date and time at which you will be making your observation. I’ve not found any web links to let you do this, so you may have to resort to a good sky charting computer program such as Guide (see accompanying chart below). You can use Guide to generate a time-specific chart showing the positions and magnitudes of the moons to help you positively identify them in the eyepiece. I was able to spot both Oberon and Titania at the 2004 Black Forest Star Party in my 13” reflector, using charts made in Guide 8.0 by Doug Nelle. Some of us spotted them at Lake Hudson a few weeks ago as well. How many can you see?

Uranus spends all of 2005 in Aquarius (the Water Bearer). There is a good finder chart for it on page 72 of the June 2005 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine. Or you can use the following web link: http://www.rasnz.org.nz/SolarSys/UranNept.htm

The following chart of Uranus and its four brightest moons was created in Guide 8.0, for August 1, 2005 at 11:00 p.m. EDT. Note that the chart is inverted with south near the top, as it would appear in an inverting telescope. Also note that the field shown is only two arc minutes across, so you can see that you’ll need plenty of magnification to pick up the moons. Of course, this chart is accurate for that date and time only. As time goes on, the moons travel in their orbits and will appear at different locations relative to the planet. (The dot near the bottom of the chart is a 15th magnitude star.)

Neptune, the next stop on our outer planetary tour, is also a gas giant. It has an equatorial diameter that is slightly less than that of Uranus, but it lies half again farther away. As a result, its angular size measures barely more than 2 arc seconds across. Its greater distance also makes it appear less bright, about magnitude 7.8 around opposition, making it strictly a binocular or telescopic object.

You’ll need good optics, steady skies, and plenty of magnification to discern its tiny blue-gray disk. You can also forget about seeing any planetary detail - at less than 2.5 arc seconds across you’ll do well just to tell it apart from a star. Fortunately, Neptune’s largest and brightest moon, Triton, is visible in moderate-sized amateur instruments, as it shines at magnitude 13.5. I also observed Triton at last year’s Black Forest Star Party.

Neptune spends all this year in Capricornus (the Sea Goat). You can use the same resources and methods described above for Uranus to locate and observe Neptune and its moon Triton.

The following chart of Neptune and its brightest moon Triton was created in Guide 8.0, also for August 1. Again, south is near the top.

Pluto, our final destination, is by far the most challenging target of our trio. Its distance and extremely small size (it’s smaller than the Earth’s moon) combine to give it a very small apparent diameter, only a fraction of an arc second across. It has a highly elliptical orbit that takes it inside that of Neptune for 20 of the nearly 250 years it takes Pluto to make one trip around the sun. This was the case as recently as 1999, but it has now moved just outside Neptune’s orbit and will stay outside until well into the 23rd century. Even at that “close” distance, though, it still shines only at around magnitude 13.8, if you call that shining. It’s even outshone by Neptune’s moon Triton!

You can forget about seeing its disk, or its moon Charon. In fact, simply finding it is quite a challenge. In my experience, you don’t really observe it - you can’t casually put it in the eyepiece and say “There it is!” It takes a little more work than that.

First, you need enough aperture and fairly dark skies. Some say Pluto can be spotted with eight inches of aperture, but I recommend at least ten. Also, you’ll need a highly detailed finder chart. As is the case for Uranus and Neptune, the June 2005 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine has a good one. You could also use a good, accurate sky charting computer program, or use the following link: http://www.rasnz.org.nz/SolarSys/Pluto.htm

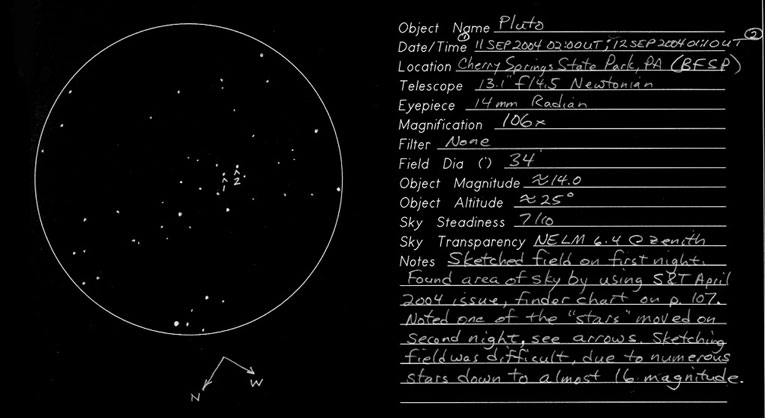

Now that you know where to find it, you’ll have to match up the field in your telescope with the finder chart. But which one is Pluto? There are likely to be so many faint stars in the field that it could make identifying the diminutive planet nearly impossible. I faced the same predicament at the 2004 Black Forest Star Party. There were so many faint stars in the eyepiece, many more than the number that were shown on the finder chart. There was no way to pick out one and say “That’s Pluto!” What I did was to sketch the field on two successive nights. Sure enough, on the second night I noticed that one of them moved, and in the predicted direction, so my identification was complete. You may need to do the same thing.

Below is the sketch and observation report I made at the 2004 Black Forest Star Party, on the nights of September 11 and 12. The position of Pluto on the two nights is labeled with the numerals 1 and 2.

Pluto spends the entire year in Serpens Cauda (the Serpent’s Tail), very close to the Ophiuchus - Sagittarius border.

The following table provides some additional information on the three outer planets. Saturn is included for comparison.

Mean |

Mean |

2005 |

2005 |

Angular |

Brightness |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Saturn |

116,464 |

9.54 |

January 13 |

Gemini |

20.5 |

0.4 |

Uranus |

50,724 |

19.2 |

August 31 |

Aquarius |

3.5 |

5.7 |

Neptune |

49,248 |

30.1 |

August 7 |

Capricornus |

2.3 |

7.8 |

Pluto |

2274 |

39.5 |

June 14 |

Serpens |

0.1 |

13.8 |

The outer planets, like so many things in life, will give you back only what you put into them. But it only takes a little coaxing and they’ll reward you for your effort. It will be effort well spent - you just may surprise yourself!