An Observational History of Mars

by Dave Snyder

Printed in Reflections: April and May 2001

(updated January 2002).

This year the

“Astronomy on the Beach” at Kensington Metropark will

focus on Mars and the International Space Station (ISS). The ISS has

generated a lot of interest recently, but why focus on Mars? I suppose the

obvious answer is that Jupiter and Saturn are past their prime for this year and

we don’t have any bright comets to work with. However Mars is a

fascinating object and besides, this June Mars will be closer to the earth than

it has been at any time since 1988.

Mars has been observed by many ancient cultures - we have no idea who was the

first to notice it. Those who did, noticed a pale pink object that was

only visible in the early morning just before dawn (and rather difficult to see

at that). This object moved relative to the stars, got brighter over the

next year and rose earlier and earlier. Then it abruptly stopped and

reversed direction. At its brightest it was the third brightest object in

the night sky (only Venus and the Moon were brighter), had an intense red color

and was visible all night long. After moving the “wrong”

direction for some 70 days or so, it stopped and reversed direction

again. It gradually got dimmer, was only visible in the evening sky and

set earlier and earlier. After another year it again was a pale pink

object, this time only visible just after sunset. Shortly after that, it could

not be seen at all. It remained hidden for about one hundred days when the

cycle repeated again. Each cycle took a little over two years.

The Greeks named this object Ares after their god of war. The Romans in

turn named it Mars after the roman god of war.

The scientific study of Mars begins in 1600 when various individuals (mainly

scientists, but a surprising number of amateurs as well) observed the planet

with telescopes. Our knowledge increased gradually, but certain

misconceptions became established, many of which persisted until the last half

of the 20th century. It is then we start to see groups (instead of

individuals) studying Mars. Some of these groups were composed of

amateurs, some were composed of scientists and some were composed of both

amateurs and scientists. The most successful of these groups was

NASA. While NASA’s primary objective was landing men on the Moon, clearly

the second item on NASA’s priority list was the scientific exploration of Mars

using unmanned spacecraft.

NASA, along with its soviet counterpart IKI, sent numerous spacecraft to the

red planet. While there were many failures, there were many successes as

well. In addition, out of the thousands of meteorites that have been

examined by scientists, a dozen or so are now known to have originated on

Mars. The data from the spacecraft and the meteorites have dramatically

changed our picture of Mars and gave us a seemingly endless set of clues to the

geology, chemistry, atmosphere and possible biology of Mars. However in

the process we seemed to have created more questions than answers.

A detailed chronology follows:

- 356 or 357 BC: Aristotle observed Mars passing behind the Moon.

We now call such an event an occultation. This convinced Aristotle that

Mars was more distant than the Moon.

- 1609: Galileo Galilei makes the first telescope observation of Mars.

He cannot detect any surface detail, but he notices it is not perfectly

round. (We now know that Mars is 100% illuminated only near opposition, at

other times it is shaped like a gibbous Moon).

- 1659: Christiaan Huygens made the first useful sketch of Martian surface

features. (Modern images of Mars show a planet with dark red regions among

lighter red regions. In the following text I will use term

“maria” for the dark regions and the term “desert” for the

light regions. This matches modern usage, but these terms were not used in

1659. However do not assume the deserts are hot dry places. Maria

often appear greenish in color but we now know this is an optical illusion.)

- With Huygens’ crude telescope, he saw one of these maria (which is now called

Syrtis Major). He observed it move that night and again the next

night. He concluded that Mars rotated on its axis with a rate of 24

hours. Huygens believed that Mars might be inhabited, perhaps even by

intelligent creatures. He shared that belief with many other scientists

who would observe Mars over the years to come.

- 1666: Giovanni Cassini conducts more careful observations. He

concludes the rotation rate is 24 hours and 40 minutes. While there is

some question on this matter, Cassini is probably the first to notice that Mars

has white spots located near the poles. For the next 300 years people

assume these spots are made up of snow, ice or both (we now call these spots

“polar caps”).

- 1719: Cassini’s nephew Giacomo Filippo Maraldi conducts some observations of

his own. After many years, Maraldi is convinced that the shapes of some

maria change over time. He thinks this is evidence of clouds that

sometimes obscure the surface. He also saw changes in the polar

caps. He speculates this showed evidence of seasons: ice from the polar

caps supposedly melted during the “summer” and freeze again during

“winter.”

- 1783: William Herschel confirms Cassini’s suspicions that Mars has

seasons. This is based partly on Cassini’s observations, partly on his own

observations, but also on the fact that Mars has an inclination that is close to

the same value as Earth’s.

- Herschel seems to be the first to refer to the maria by the term

“sea,” however he was not the first to assume that maria actually

contained liquid water. He suggests that flooding may explain some of

surface changes, though he agreed that clouds could explain some changes.

- 1860: Emmanuel Liais suggests the variations in surface features are due to

changes in vegetation (not flooding or clouds).

- 1863: Father Pierre Angelo Secchi notices that maria change color. At

different times he observed maria with green, brown, yellow and blue colors.

- 1877: Since the Earth, Jupiter and Saturn were known to have moons,

scientists suspected Mars might have moons as well. However finding them

was not easy. Asaph Hall had been searching for Martian moons, but

he found nothing. He almost gave up, but his wife insisted he keep

trying. Soon, Hall was rewarded with two small moons, which

were given the names Deimos and Phobos.

- Giovanni Schiaparelli makes a map of Mars that showed maria, some of which

were connected by thin lines. He wasn’t the first to observe them (earlier

maps show a few) but he saw more lines than his predecessors. However some

observers did not see any lines, and there was some controversy over whether

they existed at all.

- Schiaparelli assumed that these lines were natural landscape features.

He gave them the name “canali” which is the Italian word for

“groove.” However when this word was translated into English,

“canali” became “canal,” a word with a very different

meaning. This simple mistake led many people to speculate about

intelligent beings who built canals. Schiaparelli himself was unconvinced

and somewhat annoyed that his observations led to such speculation. He did

not think the lines proved anything about life on Mars, though he remained open

to the possibility.

- 1892: Edward Emerson Barnard observed craters on Mars. This

observation was almost completely ignored for over 70 years.

- Public attention was first drawn to the Martian canals, mainly through

the efforts of Schiaparelli and the French astronomer

Camille Flammarion. However Percival Lowell kept the canals in the public’s attention.

Lowell was born into a wealthy Massachusetts family and was well educated (he

graduated from Harvard). While he was aware of current astronomical theories,

he seemed more interested in other matters (which included travels to Japan).

He owned a small telescope, but there is no evidence he did any serious

observing with it. However, Lowell was well connected; among his numerous

acquaintances was the Harvard astronomer, W. H. Pickering. Lowell and Pickering

corresponded with each other on the subject of Mars.

- 1893: Lowell was given one of Flammarion’s books as a Christmas

present. This book discussed what was known about Mars, including the canals

and Flammarion’s own ideas, in particular the suggestion that the canals might

be signs of intelligent life. Lowell read the book and became obsessed with

Mars.

- 1894: Only someone with Lowell’s wealth and connections would take this obsession to

the next step. Lowell decided to build an observatory he could use to study the

red planet. He did not take the easy approach and build an observatory near his

home in Boston; rather he considered many possible locations in an attempt to

find the best seeing conditions. Seeing is a term used by astronomers; good

seeing means there is little or no turbulence in the atmosphere. Even though he

wasn’t the first to understand the importance of good seeing, it wasn’t widely

understood at the time and Lowell made a large number of people aware of it.

- Lowell convinced Pickering to join him in a trip to Arizona to scout out

possible locations. Pickering brought his assistant, Andrew Douglass and

eventually the three of them set up an observatory near Flagstaff and conducted

systematic observations of the red planet. These observations gave Lowell a

well-deserved reputation as one of the best planetary observers.

- Pickering left the observatory after a couple years, but Douglass stayed until

he was fired in 1901. That is when Douglass started doubting Lowell’s canal

observations. To fill the positions Lowell hired Vesto M Slipher, Carl Lampland

and Vesto Slipher’s brother Earl C Slipher as assistants. In 1902 Lowell was

appointed to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a non-resident

astronomer. He could have just continued with his observations and be

remembered as a skilled astronomer. However Lowell was not content to just

observe. He had numerous theories, some of which involved canals and the

intelligent creatures that supposedly built them. These theories were

internally consistent and very ellaborate.

- 1906: Lowell publishes a book “Mars and its Canals.” This

book was widely read by the general public and goes into detail on Lowell’s

ideas on the canals. He claims

the canals were built by

Martians for the purpose of transporting water from the poles to the dry Martian plains.

- 1907: Alfred Russel Wallace (a well known biologist) responded with a book

of his own in which he argued that Mars is completely uninhabitable.

Wallace used measurements of the light coming from Mars and argued that Mars has a

surface temperature of minus 35 degrees Farenheit. Lowell’s claim that

there was liquid water must be wrong. He also concluded that the polar

caps consisted of frozen carbon dioxide not water ice as Lowell and many others

had assumed.

- 1909: The available observations did not always support Lowell’s ideas. There was

growing doubt about the existence of the canals themselves, not to mention the

rest of Lowell’s ideas. When he encountered skepticism, Lowell became dogmatic

and found new audiences for his ideas by giving public lectures, writing

books and writing articles in popular magazines.

Lowell became an outcast in the scientific

community. However he had support from a few scientists. In particular,

Flammarion was always sympathetic to Lowell and his ideas.

He has become well known and respected by the general public.

- Lowell’s activities discouraged many scientists, particularly

in the United States, from studying Mars as it no longer seemed a

“serious” subject worthy of scientific pursuit.

However in Lowell’s defense, some have argued that he deserves credit for

developing modern planetology, a word Lowell invented. He originated the

notion that the Martian climate has changed over time, a notion we now believe

to be correct. He insisted that any theory of planetary evolution needed

to account for changes in all the planets not just the planet a scientist

happened to be studying. And he was the first to suggest that Mars is the

best location to test theories of climate change. This might help

scientists studying changing in the Earth’s climate. In some respects

Lowell was almost a hundred years ahead of his time. On the other hand,

his ideas on

possible Martian biology seem antiquated to the modern observer.

- 1912: Svante Arrhenius has an alternate suggestion for the Martian surface

variation: Mars might be covered with salts, during the winter the salts

have a light color. When the polar caps melt in summer, the salts absorb

water and develop a darker color.

- 1938: On the day before Halloween, Orson Wells produces a radio production

of the fictional story “War of the Worlds.” This is a story of

Martians invading the earth. The production was so convincing, that many

people believe there has been a real invasion by Martians. A panic

resulted.

- 1947: The Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) is

formed. ALPO along with the BAA (which was founded in 1890) and other

organizations coordinate several Mars observation programs. In such

programs, amateur and/or professional astronomers from around the world pool

resources. Over the next several years, these programs provide several

extended periods of almost continuous observations (because you can observe Mars

only at night, it is impossible for a single observer at a single location to do

this - but a group of observers can).

- 1952: Gerard Kuiper makes the first attempt to determine the composition of

the Martian atmosphere using modern equipment. He discovered spectral

lines that indicated carbon dioxide. For several decades, researchers had attempted to measure the

atmospheric pressure of Mars. Estimates varied over a wide range, from less

than 24 millibars to well over 90 millibars (by comparison the earth’s

atmospheric pressure is about 1000 millibars). However scientists did not think there

could be 24, let alone 90 millibars of carbon dioxide. Therefore they reasoned the remainder of the

atmosphere was made up of something else.

This was assumed to be nitrogen and argon (since these were the only non-reactive gases likely to be present on Mars that

wouldn’t have been detected by the analysis methods used at the time).

The canal controversy would not be completely resolved until spacecraft arrived

at Mars.

In the 1960’s most scientists thought there were no canals on Mars, however

there were a few exceptions, such as Earl Slipher.

He wrote several books, some of which contained photographs.

Slipher claimed these photographs

had lines in the same place as the canals of Percival Lowell.

One of these books was published as late as 1964.

That same year, after a few U. S. and soviet failures, a U. S. spacecraft,

Mariner 4, is the first to flyby Mars. In 1969, Neil Armstrong walks on the

Moon. Some consider that a manned mission to Mars is the next step. However

there are problems with the idea. A round trip would take two years. Enough

fuel and water must be carried on board so the astronauts could survive and

return to earth. The weight of that fuel and water adds to the expense. A one

way manned trip to Mars (assuming one could find anyone to volunteer for such a

thing) seemed manageable, but a round trip seemed too expensive and too

difficult. To date, it has never been attempted, but the idea has been tempting

and there are plans to send people to Mars (it remains to be seen if and when

these plans will succeed).

Since Mariner 4, the U. S. has sent several spacecraft which either flyby or

orbit Mars: Mariner 6, 7 and 9, Viking 1 and 2, Pathfinder, the Mars Global

Surveyor (MGS) and Odyssey. Odyssey was launched in April 2001 and

entered orbit around the red planet in October 2001. These spacecraft along with several soviet spacecraft have

returned thousands of photographs and a vast quantity of other data. In

addition, a dozen or so meteorites are known to have originated on Mars.

Analysis of these meteorites has supplied additional data.

We now have a very different picture of Mars. Some parts of Mars have numerous

craters suggestive of Mercury and the Moon, but other parts of Mars have plains,

volcanoes, canyons and river channels. The volcanoes and canyons are bigger

than any other known examples, however there is a vague similarity between some

of these features and similar features on the Earth. There was no evidence of

canals or liquid water.

However data prove Mars was warmer and had abundant liquid water in its early history.

Today there is still water, but almost all is in the

form of ice in the polar caps and below the surface (some locations on Mars may

experience temperatures above the melting point of water,

hence transient pools of liquid water are possible). There is also the

possibility Mars may have had tectonic plates like the Earth does now (if so,

they were active for only a 500 million years or so).

We now know that the

atmosphere has a pressure that varies between 5 and 10 millibars (much lower

than anyone had suspected until Mariner 4 made radar occultation measurements).

It is almost entirely carbon dioxide, but contains some water vapor and other

trace gases. The polar caps are partly water ice and partly frozen carbon

dioxide, but there are differences between the northern and southern polar caps,

as there is between a polar cap seen in the Martian winter and a polar cap seen

in the Martian summer.

Since the canals are not real, why were Schiaparelli, Flammarion and Lowell

(among others) so convinced they were real? There are some clues. First, Schiaparelli was

colorblind and this may explain why he saw details others did not. Once

Schiaparelli’s results were known, the power of suggestion may have influenced

other observers. Also, records suggest most observations of canals happened

under poor seeing conditions or when small apertures were used. The canals

disappeared under better conditions and larger apertures. Lowell preferred to

reduce the aperture of his scope (which made observing the canals easier), but

many of his critics used larger apertures.

There also have been a few tantalizing clues suggestive of life, but to date no

proof that Mars has or ever had life. The most publicized of these clues was a

meteorite that was given the designation ALH84001. ALH84001 is one of the dozen

or so meteorites known to come from Mars and had what looked like fossils. Some

scientists believe these fossils come from ancient Martian bacteria, however

other scientists are not convinced. I should note that Viking photographs in

the region known as Cydonia look like a human face, but MGS photographs of the

same region look like a pile of rocks. A few non-scientists claim this is a

structure built by Martians, however that is unlikely.

There is currently a spacecraft enroute to Mars; it was launched by Japan

in 1998. There were some technical problems, but it is expected to arrive at

Mars in late 2003.

Anyone with a telescope can attempt to observe Mars themselves. The best time

to observe Mars is the couple months before and after opposition (the next opposition is in the

year 2003). The rest of the time, it is difficult to see

any detail. Every 15 years there is an exceptionally good opposition; the last

one was in 1988, the next one is in 2003.

Observing Mars takes practice. Details become clear after a little acclimation.

If the seeing is bad, you will not observe as much detail as when the seeing is

good so patience is important. You should try to observe Mars as often as

possible during the opposition, this will allow you to track changes in surface

and atmospheric features. When you observe Mars, you may want to try sketching;

this will train your eye to observe detail. Generally the polar caps are the

easiest features to see, however you should see the maria and deserts as well.

If you observe over long periods and are patient, you may see clouds, dust

storms and various atmospheric phenomena. You may also notice changes in the

polar caps and the maria.

If you have a good telescope and sharp eyes it may be possible to see the two

moons, Phobos and Deimos. At best they have magnitudes 11 and 12, and are

rather close to the bright red Mars.

Observers have seen various types of clouds on Mars. They are known by the

labels blue, white, yellow and W-shaped. These labels can be misleading.

Yellow clouds look yellow to the eye, however blue clouds do not necessarily

look blue, white clouds do not necessarily look white and W-shaped clouds are

not always W shaped. Yellow clouds are composed of dust and sometimes grow to

cover much of the Martian surface, when this happens it is known as a dust

storm.

Having the correct equipment will help your observations. If you wish to

observe surface details, a dark yellow, red and/or orange filter is helpful.

Violet and blue filters are helpful if you want to observe clouds and other

atmospheric phenomena (but not yellow clouds or dust storms). Green filters are

helpful for observing the polar caps and other white areas, yellow clouds and

dust storms. If you have made either Jupiter or Saturn observations, you may

want eyepieces that provide slightly more magnification than the eyepieces you

used for Jupiter and Saturn.

One phenomenon worth mentioning is the violet clearing. When Mars is observed

through a blue or violet filter, it usually appears as a featureless blob (but

clouds can sometimes be observed). However on occasion (usually only once every

few years) details on the surface appear. This lasts a few days; such events

are known as violet clearings. It has been suggested this demonstrates a poorly

understood change in the Martian atmosphere, but the best evidence suggests it

has nothing to do with the atmosphere at all and is probably an optical

illusion.

For more information

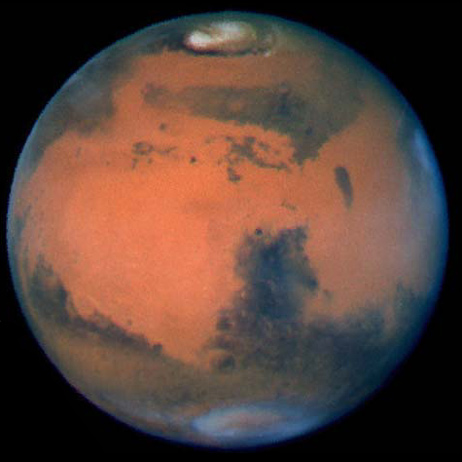

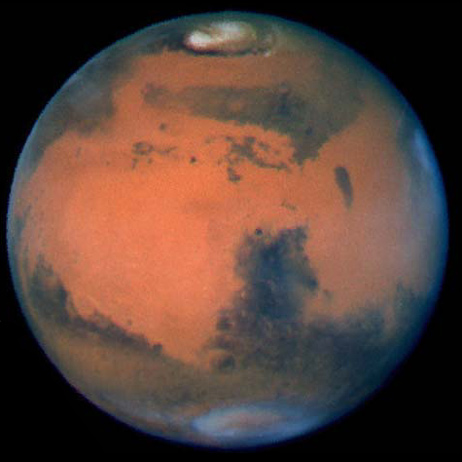

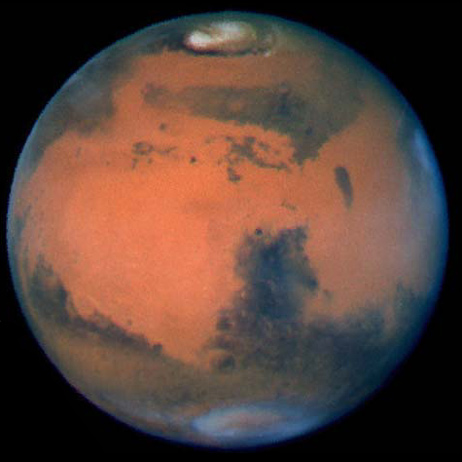

The Mars photo above is from the Hubble Space Telescope

Wide Field Planetary Camera-2. It was taken on March 10, 1997,

just before opposition and just before summer solstice.

The white area at the top of the photo is the permanent north polar cap.

A haze can be seen in the equatorial

region. The dark area near the center of the photo is Syrtis Major.

See also:

Photo Credits

Credit for the Mars photo: David Crisp and the WFPC2 Science Team (Jet Propulsion

Laboratory/California Institute of Technology).

Links

Copyright Info

Copyright © 2015, the University Lowbrow Astronomers. (The University Lowbrow Astronomers are an amateur astronomy club based in Ann Arbor, Michigan).

This page originally appeared in Reflections of the University Lowbrow Astronomers (the club newsletter).

This page revised Tuesday, April 10, 2018 7:08 PM.

This web server is provided by the University of Michigan;

the University of Michigan does not permit profit making activity

on this web server.

Do you have comments about this page or want more information about the club? Contact Us.