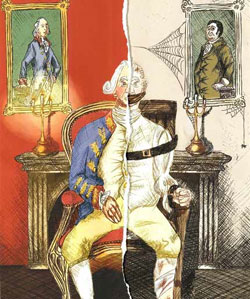

King George III

During his reign from 1760 - 1820, King George III became the model for the “perfect Englishman” in the latter half of the eighteenth century. From the beginning of his reign, he exhibited desirable qualities of self-discipline, composure and temperance. However, in 1788-89, he fell ill, both mentally and physically. The King’s madness posed a threat to the state’s stability and thus became a popular theme in many representations. His madness was associated with a loss of reason and as the eighteenth century was the Age of Reason, this unreason was undesirable. However, the public was sympathetic of the King’s illness and celebrated the King’s recovery. This is evident in the caricature “House-Breaking, before Sun-Set,” which at first glance seems to depict only the political instability at the time. However, a closer analysis reveals a crown with “Obscured, not Lost” in the background to suggest that there is hope for order once again 13.

Following his publicly known mental illness, public acceptance and awareness of mental illness grew. Patient admittance in private asylums increased significantly during this period. We cannot definitively say the same for public asylums because it was only three decades later that they began to keep patient records. This influx of patients into asylums has been argued to be a way of re-establishing control by containing the infection, since madness was considered contagious 14.

Overall, King George III experienced five significant episodes of madness. It was thought to be a psychiatric disorder at the time. However, in 1969, following an examination of his documented symptoms including red urine, lameness and temporary mental confusion, it was proposed that King George III’s madness was symptomatic of a rare genetic blood disorder known as porphyria 15. The lead researcher, Dr. Warren, claimed that people with porphyria have a gene that makes them more prone to episodes of mental attack but rarely show any symptoms. This disorder is worsened by mercury and lead. Thus, Dr. Warren and his fellow researchers tested the King’s hair for traces of these metals. However, instead of finding these metals, they found very high levels of arsenic (17 parts per million was found. Less than one part per million is usually found), which is another metal that worsens porphyria. This is because arsenic interferes with the production of a vital part of blood: heme, which is also what the faulty gene affects.

A more recent study conducted in 2005 has revealed high levels of arsenic in the King’s hair. The even distribution of arsenic along his hairs suggests that it is within the hairs themselves rather than being a result of preservative arsenic that museums often use. They have suggested arsenic to be the cause for the madness he exhibited 16. However, toxicologist John Henry from Imperial College in London warns against this theory because high levels of arsenic in the King’s hair only shows that he had significant amounts of arsenic in his body in the last few months of his life but does not prove that it caused an illness he had during his entire life. Furthermore, King George III’s medical records show that he was prescribed a mineral medicine containing antimony for his abdominal pains, which is usually found alongside arsenic.