The interest in satellites led to the idea that the United States should establish a permanent space agency. The panel started drafting ideas for a „National Space Establishmentš to conduct space research and applications and manned exploration of outer space. The original rocket panel created a „Committee of the Occupation of Spaceš during September of 1957, chaired by Homer Newell. This was the first of many steps to formalize a potential interest in satellites and space. Michigan‚s Nelson Spencer was a member of this 4-man committee that promoted the development and demilitarization of space research.

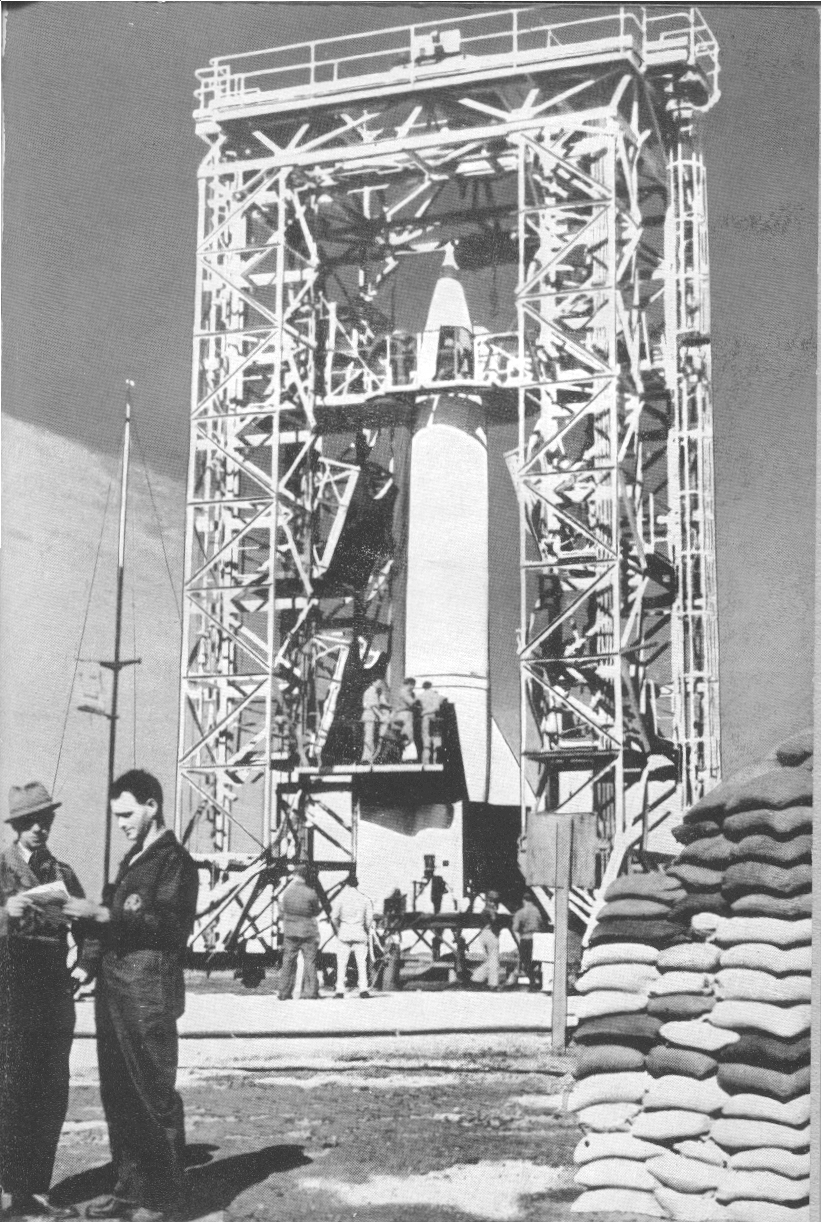

On Friday, October 4, 1957, the launching of the Russian satellite, Sputnik, forced organizations throughout the United States to undertake a serious appraisal of their scientific resources. While the United States‚ satellite project, Vanguard, was still in the works, the Soviet Union had a much larger satellite already flying overhead. At Michigan, President Hatcher appointed a seven-member Special Science Advisory Committee to evaluate the university‚s science instruction and research. The Committee advised the President and deans of the potential space-related research in several areas. Another faculty committee was formed to stimulate interest in the space sciences, chaired by Professor R.B. Morrison, Director of the Aircraft Propulsion Laboratory in the Department of Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineering. The Space Sciences Committee surveyed departments and laboratories, compiling a list that showed that the research interests of over 200 faculty and staff were directly relevant the space sciences.

On a national level, Sputnik created a new sense of urgency for the federal government to put together a national space program. Nelson Spencer proposed that the Rocket Panel meet in Ann Arbor to draft a proposal for a civilian space administration, which would conduct the national program for space research and exploration. On November 13-14, 1957, the panel met at U of M‚s Michigan League and issued a paper called „A National Mission to Explore Outer Spaceš on November 21, 1957, which was sent to Detlev Bronk, president of the National Academy of Sciences; James Killian, the President‚s science advisor; and Lee DuBridge, president of the California Institute of Technology. Killian referred the group to the President‚s Science Advisory Committee, who was also exploring the United States role in space exploration.

In December 1957, the group expanded its membership from those involved in upper-atmosphere research to include people who would add weight to its recommendations. Members were added in the areas of military research, industry, and rocket development. This included the American Rocket Society, which was also pushing the idea of a national civilian space agency.

The RSRP and the American Rocket Society worked together to develop a summary in January 1958, supporting a „National Space Establishmentš to have responsibility for investigating and exploring space. Along with the summary, the groups mapped out a plan to put this idea into motion and get it in the hands of someone who was in a position to act. They contacted congressmen, officials in administration, the Academy of Sciences, and Vice President Nixon. Through the Vice President, the group was able to meet with the Atomic Energy Commission, the U.S. Information Agency, and the staffs of the House and Senate committees that were working on the task of responding to the Soviet challenge in space. At the time, they shocked their audiences by suggesting that the agency would require as much as a billion dollars a year, and that the space program could eventually become comparable to the atomic energy program.

The need to form a space program was apparent, but the question still remained as to how to organize it. There were three options available: create new agency, assign responsibility to an existing agency (like the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or NACA), or include it in Department of Defense.

To many members of the scientific community, NACA was regarded as extremely conservative. Both the RSRP and the American Rocket Society considered it unprepared to take on space research on the scale that they deemed necessary. Some felt that it would be a great error to set such an organization up outside the jurisdiction of the Department of Defense. This idea, members of the RSRP were afraid, would take the emphasis off the scientific research in favor of military applications. The goals of the U.S. space program were to provide research opportunities and results to several institutions, both inside and outside the government, the military, and even the United States. Thus, according to the panel, in order to be successful the organization must be civilian. President Eisenhower also agreed that the best relations could be kept with other nations if the space program was civilian run, and not military.

Doubts about NACA did not suppress the satisfaction

when the National Aeronautics and Space Act was passed on July 29, 1958.

The RSRP gave its support to the newly created National Aeronautics and

Space Administration (NASA), which used NACA as a base. According

to the National Aeronautics and Space Act, „it is the policy of the United

States that activities in space should be devoted to peaceful purposes

for the benefit of all mankind∑The Congress further declares that such

activities shall be the responsibility of, and shall be directed by, a

civilian agency exercising control over aeronautical and space activities

sponsored by the United States∑š Now, however, the purposes of the

Rocket and Satellite Research Panel were to be fulfilled by NASA, and the

Rocket Panel eventually suspended operations as an individual organization.