|

|

last modified: Sunday, December 18, 2005 8:17 PM |

|

Wal-Mart Is Coming to Town: What Can You Do, What Should You Do? |

|

William Kaplowitz |

wmkap@umich.edu |

A New Wal-Mart is a Mixed Blessing, if a Blessing at

all

It’s been said that the second worst thing that can happen to a community’s economy is for a Wal-Mart store to move in. The worst is for that Wal-Mart store to move to the community next-door. There will be the same depressing effect on wages and similarly disastrous effects on competing local businesses, but the community won’t even be able to capture any of the tax dollars generated by Wal-Mart. This witticism reflects a common view among advocates of local economies and the progressive community: Wal-Mart is bad news. [1]

Of course, not everyone shares this view: There are those who say that Wal-Mart is not, in fact evil. They claim that Wal-Mart provides a net economic benefit by providing goods at cheaper prices. A Cato Institute economist estimates that Americans save $100 billion per year by shopping at Wal-Mart. Even Democrats acknowledge that many people appreciate this. Clinton Administration Secretary of Labor Robert Reich noted that “we as consumers say ‘hurray’” to Wal-Mart’s low prices. [2]

Defenders of Wal-Mart also claim that Wal-Mart does not achieve its low prices by oppressing its workers. They reason as follows: Wal-Mart is able to recruit workers in a fair and open labor market. Ipso facto, it must pay them a fair wage – if their labor were worth more, they would not accept Wal-Mart’s wages. Labor activists claim that were Wal-Mart to increase all of its prices by just a penny, it could pay its workers – who, it is estimated, make between $7 and $8 per hour [3] -- $1 per hour more. [4] These low wages ultimately cost tax-payers quite substantially. A Congressional committee has determined that the average Wal-Mart employee requires $2,100 per year in public assistance for things look school lunches. [5]

It is asserted that the location of a new Wal-Mart store in a community provides a great benefit to local school districts and other institutions that depend upon property taxes. It is claimed that the sheer size and value of a Wal-Mart super center can make a major impact on tax rolls, all without creating any new consumers of school district services. As one exuberant Philadelphia area school district business manager said, "From a school district standpoint, anytime we can bring in a property that has a fairly high assessment and there's no kids being produced from that property, it's pretty exciting." [6]

However, several studies suggest that the true impact of new Wal-Mart or other Big Box stores is far less rosy. [7] These studies have concluded that new commercial development can negatively impact local communities in two ways that the exuberant school district business manager above neglected. First, municipalities often incur enormous infrastructure costs in preparing for such large-scale development, which outweigh the increase in property taxes generated. This leads to property taxes going up, not down. [8] Second, large new commercial development can often drive local businesses out of the market, and can negatively impact local residential property value as well. [9]

What Communities Can Do to Keep Wal-Mart Out.

So how can communities protect themselves? Two main strategies are used. First, in an effort to pre-empt Wal-Mart’s forays into a community, some communities have passed Size Caps that limit the amount of area that a retailer occupy. These have been relatively successful. Second, Big Box retailers need their parcels rezoned for Big Box development before they can build. Rezoning requests are usually approved, but opponents of Wal-Mart can challenge these approvals at the ballot box and in court. Ballot referenda are often successful, although there have been some notable failures. Legal battles to overturn rezoning approvals are often quite costly, and have not succeeded frequently. Other less direct measures, like living wage ordinances, historic preservation laws, and environmental impact reports may be used to harass discourage or prevent Wal-Mart from locating a store in a community. [10] Between 1993 and early 2004, 215 communities had successfully fought Wal-Mart and other big box retailers. [11]

Size Caps

One

strategy is to pass a “Size

Cap.”

[12]

Such Size Caps can be voted on directly

or passed by elected officials.

[13]

In response to such caps, retailers may

try to divide their operations into two neighboring stores. Communities

may defeat such schemes by structuring their zoning ordinances such that

retailers occupying multiple buildings are considered a single retail use

for purposes of the cap.

[14]

One

strategy is to pass a “Size

Cap.”

[12]

Such Size Caps can be voted on directly

or passed by elected officials.

[13]

In response to such caps, retailers may

try to divide their operations into two neighboring stores. Communities

may defeat such schemes by structuring their zoning ordinances such that

retailers occupying multiple buildings are considered a single retail use

for purposes of the cap.

[14]

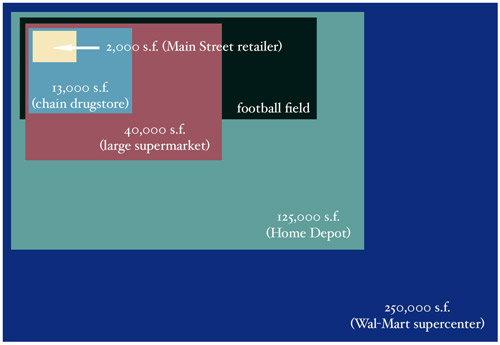

The City of Charlevoix, Michigan, now restricts stores to 45,000 square feet, about the size of a large supermarket. [15] See Figure 1, ‘How Big Is Big?,’ which illustrates the enormous differences in scale among different types of retailers. [16] As the opening aphorism pointed out, this would be worse than disastrous if there were not similar bans beyond the city’s boundaries. Fortunately, the surrounding township, Charlevoix Township, has also passed a size cap, although less restrictive, which caps stores at 90,000 square feet – whereas a typical Wal-Mart Supercenter is 250,000 square feet. [17] In addition, the Charlevoix ordinance subjects parcels over 20,000 and 50,000 square feet to increasingly strict review and permitting requirements, including traffic studies and a plan to reuse the building should it become vacant. [18]

In other areas, size caps have been passed at the neighborhood level. [19] By greatly limiting the potential sizes of new retail users these ordinances make a community less attractive for Wal-Mart expansion, and will soften the (negative) economic impacts of new Big Box retailers.

Major advantages of Size Caps are that they are not done on a parcel-by-parcel basis, and they can be passed before Wal-Mart and its lobbyists show up.

Fighting Rezoning Approvals in Court and at the Polls.

Local officials are often excited by the short-term promise of Wal-Mart are other new development, and often approve rezoning requests submitted by developers. In many communities, concerned citizens can challenge such approvals by collecting signatures to put the rezoning on the ballot. Such an initiative to reject the rezoning of a parcel for Wal-Mart was recently passed in Lorain Ohio. [20] The initiative was organized and supported by a group of concerned citizens who were victorious despite spending less than $3,000. Wal-Mart spent over $150,000 to defeat the initiative. [21] Such referenda are not always successful. In referenda in Casa Grande, Arizona [22] and Sandy, Utah [23] , voters approved the rezoning of parcels to allow Wal-Mart stores.

Other citizens have challenged the legality of rezonings on procedural grounds, with limited success. [24] In Casa Grande, Arizona, a rezoning for a new Wal-Mart was put to a referendum, and the rezoning was approved. Two citizens then brought suit alleging that the city failed to comply with notice requirements, and requested that Arizona courts therefore nullify both the referendum and the underlying rezoning. These citizens owned property within 200 feet of the parcel in question, and so the City was required by Arizona law to notify them. However, the property to which the City mailed the notice is not occupied by those citizens, and so the citizens did not receive timely notice. The City was also required to notify the general public through newspaper ads, and did so. The Arizona Supreme Court held that the citizens could have brought suit before the referendum occurred. Having failed to do so, they could not sue to have the referendum overturned because proper notice of the rezoning had not been given.

Conclusion

There is ample evidence to suggest

that Wal-Mart stores are not good for America’s local economies. Concerned

citizens have several tools available to them in their efforts to protect

their communities. In those communities where there is a

strong sentiment in favor of preserving local character and local businesses,

as in Charlevoix, MI, it may be possible to pass a Size Cap. Where

such political will exists, Size Caps – which are general and preventative – are

probably the best way to protect a community. Most

other strategies involve either enormous legal bills, or the great risks

inherent in any political campaign.

[1]

See, e.g., New Rules Project: Hometown Advantage: Big

Box Economic Impact Studies: Existing Business and Jobs. http://www.newrules.org/retail/econimpact.html#4,

accessed 11/13/2005; Coop America: http://www.coopamerica.org,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[2] ABC News, November 11, 2005: “Wal-Mart Greedy Villain or a Shopper’s Best Friend.” Available at http://abcnews.go.com/2020/Business/story?id=1303587, accessed 11/13/2005.

[3]

Basker, Emek, 2004: “Job Creation or Destruction:

Labor-Market Effects of Wal-Mart Expansion.” Available at http://econwpa.wustl.edu/eps/lab/papers/0303/0303002.pdf,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[4] ABC News 2005.

[5]

see Website of Rep. George Miller, who commissioned

the report: http://edworkforce.house.gov/democrats/releases/rel21604.html,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[6]

Boyertown Area Times, November 11, 2005: “Is Wal-Mart

Good for Boyertown?” available at http://www.zwire.com/site/news.cfm?newsid=15561779&BRD=2694&PAG=461&dept_id=552976&rfi=6Accessed

11/13/05.

[7]

See, e.g., RKG Associates: Understanding the Tax Base

Consequences of Local Economic Development Programs, available at http://www.rkg1.com/pdfs/taxbasemgmt.pdf,

accessed 11/13/2005; DuPage County Development Department, October 1991. “Impacts

of Development on DuPage County Property Taxes,” available at http://www.newrules.org/retail/econimpact.html#4,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[8]

DuPage County Development Department, October 1991.

[9]

RKG Associates.

[11]

Traverse City Record-Eagle, April 11, 2004: “Crusade

Against Wal-Mart.” Available at http://www.record-eagle.com/2004/apr/11wal.htm,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[12]

New Rules Project: Hometown Advantage: ‘Election

Results.’ November 9, 2005. http://www.newrules.org/retail/news_slug.php?slugid=323 accessed

11/13/05

[13]

see New Rules Project: Hometown Advantage: ‘Size

Caps.’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/size.html,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[14]

ibid.

[15]

New Rules Project: Hometown Advantage: ‘How Big

is Big?’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/howbigisbig.html accessed

11/13/05

[16] ibid.

[17] ibid.

[18]

New Rules Project: Hometown Advantage: ‘Retail

Business Size Cap – Charlevoix, Michigan.’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/charlevoix.html,

accessed 11/13/2005.

[19]

New Rules Project: ‘Size Cap.’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/size.html.

[20] New Rules Project: ‘Election Results.’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/news_slug.php?slugid=323

[21]

ibid.

[22] see Zajac v. City of Casa Grande, 209 Ariz. 357 (2004), available at http://www.supreme.state.az.us/opin/pdf2004/CV030397PR.pdf, accessed 11/13/05.

[23]

New Rules Project: ‘Election Results.’ http://www.newrules.org/retail/news_slug.php?slugid=323

[24]

see, e.g., Zajac,

209 Ariz. 357 (2004), available

at http://www.supreme.state.az.us/opin/pdf2004/CV030397PR.pdf accessed

11/13/05