|

|

last modified: Friday, December 16, 2005 0:21 AM |

|

Growing Locally Owned Business: Innovative Strategies |

|

Samara Freemark |

samaraf@umich.edu |

This entry will examine innovative strategies that can be used on the local level to encourage small business creation in economically under-served areas. I will work from the premise that locally owned businesses are inherently good for communities in that they increase local wealth; help reduce the ‘leaky bucket' effect by keeping money circulating within local economies; encourage the formation of a merchant class with a physical stake in their community; allow local citizens to serve as entrepreneurial role models; increase local employment; help foster environmentally healthy economies that rely less on long-distance shipping; and buffer communities against the vagaries of larger economic trends.

This entry examines four innovative models for small scale business development and maintenance: microlending, the SHARE program, local currencies, and business networks. Because these programs have not been tested extensively, few conclusions can be drawn as to their applicability to all areas or populations. Still, they offer intriguing visions of the potential of local economies.

For further reading, see Michael Shuman, Going Local: Creating Self-Reliant Communities in a Global Age. The Free Press, New York. 1998.

Accion USA: Microlending in the United States

Microlenders issue small loans for business startup and development, and they lend where others won't: to borrowers without collateral, to under-served rural and urban communities, to untested entrepreneurs. Archetypal examples come from the developing world: Latin America's Accion International and the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh, whose name has become synonymous with the field. Microcredit has been attempted on a relatively small scale in the United States, primarily through the work of Chicago's Shore Bank and Accion International's Stateside branch, Accion USA.

Accion USA offers loans from $500 to $25,000 for a period of three to sixty months. Unlike a standard loaning entity, Accion evaluates loan applicants on qualitative measures as well as on standard measures such as collateral and credit history. Accion employees visit potential borrowers, weigh personal references, and consider subjective measures such as initiative and drive. Their borrowers are 87% minority, 35% female, and 55% low income by federal HUD standards.

In Measuring Client Success: An Evaluation of Accion's Impact on Microenterprises in the United States (1998), Hines and Servon find that Accion borrowers saw their incomes rise by an average of $455 a month and their average monthly business profits go up by 42%. Accion itself has grown exponentially, more than quadrupling its client base in six years.

Year |

Active Clients |

Active Portfolio |

Amount Lent |

Average Loan |

1997 |

998 |

$2,667,093 |

$3,528,210 |

$2,955 |

1998 |

1,074 |

$3,594,338 |

$4,143,534 |

$3,347 |

1999 |

1,464 |

$5,229,000 |

$5,267,000 |

$3,572 |

2000 |

2,100 |

$9,718,375 |

$10,242,658 |

$5,218 |

2001 |

3,247 |

$16,854,291 |

$15,648,989 |

$5,191 |

2002 |

3,807 |

$20,719,991 |

$18,432,965 |

$6,328 |

2003 |

4,355 |

$23,913,353 |

$19,496,044 |

$6,303 |

Accion USA growth 1997-2003. Table from www.accionUSA.com

Accion's impressive growth suggests that microlending could conceivably play an important role as part of more general development strategies. For example, localities could contract with microlenders to provide financial and support services as part of a broader welfare and economic development program. However, a caveat is necessary. American microlenders have as yet been unable to match the remarkable success of the Grameen Bank, and they have had to modify the original model to better fit the American context. Though Accion does offer business startup loans capped at $10,000, the bulk of its recent funding has been targeted to entrepreneurs looking to improve or expand preexisting businesses. These loans tend to be safer than startup loans, since experienced entrepreneurs are statistically more reliable borrowers. This tactic keeps microcredit default rates relatively low, but it may limit the usefulness of microcredit as a tool for invigorating the economies of the poorest American communities.

See: Gregory Claxton, Microcredit Strategies for Assisting Neighborhood Businesses on this Economic Development Resource Page for a detailed analysis of the international roots of microfinance and the possibilities and limitations of microcredit as an American economic development strategy.

Also, Samara Freemark, Group Lending in the United States: Experiences, Complications, and Possible Re-Envisionings

Other Microcredit Resources and Organizations:

Christina Hines and Lisa Servon. 1998. Measuring Client Success: An Evaluation of Accion's Impact on Microenterprises in the United States. Washington.

http://www.accionusa.org/: Website of Accion USA.

http://www.microfinancegateway.org/: online resource for the microfinance industry.

http://www.microenterpriseworks.org/. Website of the Association for Enterprise Opportunity, the national association of microenterprise organizations.

http://www.sba.gov/: website of the Small Business Administration

SHARE: Variation on the Microcredit Model

The Self-Help Association for a Regional Economy (SHARE), based in the Southern Berkshires, was established by Susan Witt and Robert Swann in 1981 and lasted until 1992, during which time it administered twenty-three loans. SHARE was established to address the lack of credit available to small borrowers in the region, and was discontinued when local banks began to issue small business loans.

SHARE provides an example of a microlending model whose small size enabled it to loan at reasonable interest rates and achieve 100% repayment rates. SHARE recruited a network of community members who deposited money into interest-bearing savings accounts at a local bank. Their investments were used to provide small loans to local businesses. Decisions as to which loans to collateralize were made by the investors, who were personally familiar with the applicants. Because community money financed the loans, community members had a stake in supporting the borrowing business.

The SHARE model is unique in that it collapses distinctions between borrowers, depositors, and investors, but it may be limited in its scope. SHARE's success depended on strong preexisting social networks; its remarkable repayment rate can be attributed to the fact that loans were made only to people whom lenders personally knew to be trustworthy. Also, the close-knit community of the Berkshires created social incentives and pressures to repay. In this respect, the SHARE program's credit unions functioned very much like Grameen's lending circles.

The SHARE model may not be applicable to less-connected regions, but it can theoretically provide a useful development device to small regions with high social capital and lack of credit access. Operationalizing a similar program would, however, require organizers with experience in community organizing, meeting facilitation, business support, and banking. This is a tall order, especially for small towns and rural regions.

Local Currencies

Local currencies, which are also known as ‘community currencies' or ‘complementary currencies', encourage local spending and support locally owned businesses. There are approximately 200 local currencies currently in circulation in the United States.

The values of local currencies are based on a range of standards: labor hours, gold, a ‘market basket' of local commodities (as with the Constant in Exeter, New Hampshire), or the US dollar. Most local currencies are taxed at the same rate as US dollars and are subject to the following legal conditions: they must have a dollar equivalent (for purposes of the Internal Revenue Service); they must be easily distinguishable from US currency; and they must be worth at least one US dollar. ‘Time dollars', which take an hour of labor as their basic unit of value, are not taxed because they are considered primarily charitable and are backed only by bonds of ‘mutual obligation'.

The Ithaca HOUR: A Dollar-Equivalent Local Currency

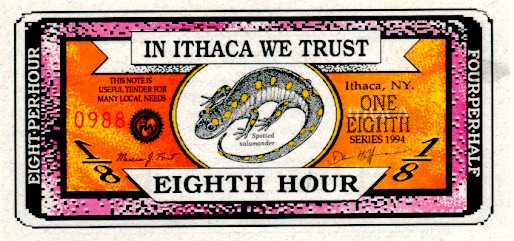

The Ithaca HOUR has been in circulation since 1991, has been used in an estimated $5,000,000 worth of transactions, and is now accepted in over 900 local businesses. The currency is administered by a Circulation Committee that prints and regulates HOURs, compiles a public directory of system participants, and recruits businesses into the system. The HOUR, which when launched was based loosely on the value of one hour of labor, is worth ten US dollars.

When a business joins the HOURs network, it is listed in the directory and receives two HOURs. Every eight months, participating businesses receive another HOUR. These issuances fuel the gradual expansion of the HOURs system, and the moderated rate at which currency is entered into circulation helps prevent inflation. New HOURs are also circulated when the Committee makes grants to community organizations and capacity-building loans to local businesses. These loans are offered at a zero percent interest rate and are expected to be repaid within six months. Most are microloans on the order of ten to one hundred HOURs (USD $100-1,000). However, in 2000 the Board issued its largest loan to date: 3,000 HOURs (USD $35,000) to the Alternatives Federal Credit Union. The loan will be used to finance five percent of the contract work to build a new headquarters for the union. This loan, like smaller ones, was offered at zero percent interest and will be repaid over ten years.

Local dollar-value currencies have been instituted in regions as diverse as the Berkshires, North Carolina's Research Triangle Park, and the Bay Area. Though boosters' claims- that local currencies have produced notable benefits to local businesses- are as yet unsubstantiated, the extent of Ithaca's program suggests that local currencies can have real effects on local economies. Like the SHARE program, however, local currencies are probably most appropriate in regions with high social capital. Because consumers do not realize any additional monetary gain when they use local currency, currencies will only succeed in cities where the emotional benefit of supporting the local economy is worth more than the inconvenience costs of juggling a second form of money.

One eight of an HOUR, worth USD $1.25. Image from http://www.ithacahours.org/

Other Local Currency Resources and Organizations

Jane Jacobs, Cities and the Wealth of Nations. Random House, Toronto. 1985.

http://www.localcurrency.org/: website of the Local Currencies in the 21 st Century Conference, June 25-27, 2004.

http://www.complementarycurrency.org/: Resource website of complementary currencies around the world. Of particular value is the ccDatabase, a collection of

information on various local currencies, which can be linked to from the Complementary Currency webpage.

http://www.timedollar.org/: General website for Time Dollars, a form of local currency based on work time.

http://www.ithacahours.org/: Website for the Ithaca HOUR

http://www.newciv.org/ncn/moneyteam.html: Alternative Money website

CCD and BALLE: Local and National Small Business Networks

Local business networks can help locally owned stores gain a competitive advantage over chains. Networks organize and advocate for locally owned businesses, ideally creating political constituencies strong enough to balance the lobbying power of larger corporations. Most serve a development role as well, organizing conferences and facilitating personal connections that encourage collaboration and skills-sharing. Conferences often lead to the creation of local purchasing and supply webs that help local businesses support each other and, in some cases, reduce costs. Most networks also run buy-local campaigns and publish free local business directories. On the intracity level, business associations, recognizing that malls draw customers not just because of the products they offer but also because they are clean, safe, and have predictable hours, have gotten savvy. The Philadelphia Center City District (CCD), for example, represents downtown businesses. CCD collects dues that go towards installing additional street lighting and landscaping, promoting Center City as a shopping destination, and funding private street cleaners and safety patrols (with euphemism worthy of Wal-Mart, these patrols are alternately called 'community service representatives' and 'goodwill ambassadors' in CCD's literature). CCD has also worked to standardize business hours to make the local shopping experience more efficient and user-friendly.

Many local networks and associations participate in national membership organizations. The Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE) is one such network. BALLE was founded in 2001 as an organization of local business networks “committed to promoting environmentally sustainable and socially responsible business practices, with a special focus on creating strong local 'living economies.'" (from BALLE's website). BALLE provides support to local networks, sponsors skill-building conferences, advocates for local businesses in the political arena and in the media, and maintains a directory of ‘sustainable' businesses. It also helps local networks organize buy-local campaigns.

Philadelphia's Buy-Local Campaign Slogan: “My City Is My Business”

BALLE is only one of several national small business networks. Others include the Social Venture Network (SVN) and Business for Social Responsibility (BSR), which have different tactics but similar goals.

National organizations such as BALLE, SVN, and BSR, and the local networks that they support, offer an alternative vision of business in America. Networks help small business adapt to competition from chain stores and from imported goods. However, networks function better as defense than offense: while they can help protect and make viable local businesses, they have limited use in business creation. Thus, local networks are most applicable in areas that already have some business presence, especially in dense urban areas with potential business concentrations. National networks, as they build membership bases, should also concentrate on those areas.

Local Business Network Resources:

www.centercityphila.org: Website of Philadelphia's Center City Business District

http://www.livingeconomies.org/: BALLE website.

http://www.svn.org/: Social Venture Network website.

http://www.bsr.org/: Business for Social Responsibility website.

A general theme, one with discouraging implications, emerges in this entry. Many alternative business development schemes, including those addressed here, are only possible in regions with high social capital. The hardest hit urban areas, where social capital is low and a local economy practically nonexistent, will have to look elsewhere for solutions. How to develop the local economies of these regions is a far more difficult question, one well beyond the scope of this entry.