|

|

|

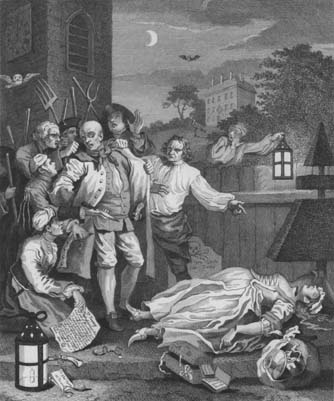

Public Execution-A Tale of Two Centuries Prosecution Ladies and Gentlemen of the jury, I would like to take you on a journey today, a journey to one of the darkest sides of eighteenth-century England’s past. Issues of capital punishment, let alone public execution, involve issues of justice, the character of authority, and most important, the respect for human life. Even if we were to agree upon the merits of capital punishment, the very idea of making such a gruesome act public instantly offends our ethical sensibilities. Our journey today begins in a crowded London square. The square grows increasingly crowded, more and more people squeeze together; there is an air of tension and delight, the City Square has an atmosphere unlike anything you have ever experienced. This is not a crowd gathered for some festive celebration, nor is it a gathering for some tragic communal experience: a loss of a war, the illness of a king. NO, you are now in a square in London, exactly two hundred years ago, about to witness a public execution. It is important to note that the people of the eighteenth century were not a vastly different kind of people we are today. Like us, English citizens felt that the way a person died was important, "it was expected that good people die well, and that the good and the great would die well."(1) During the eighteenth century, a small resistance was accruing to the notions of capital punishment and public executions alike. As my first witness, I now call the reputed English philosopher, David Hume, author of Treatise of Human Nature, to the stand. [David Hume takes an oath and seats himself in the witness box] Prosecution Mr. Hume, have you ever been a witness to a public execution? Hume Yes, good sir, I have. The execution I have famously witnessed was that of our late, great King of England,Charles 1. Prosecution How was the King Charles I executed? Hume He was beheaded. Prosecution Would up please describe to the people of this court the aftermath this particularly bloody execution had on the general population of England? Hume Well, "it is impossible to describe the grief, indignation, and astonishment, which took place…throughout the whole nation, as soon as the report of his fatal execution was conveyed to [the English people]. Women are said to have cast forth the untimely fruit of their womb: Others fell in convulsions, or sunk into such a melancholy as attended them to their grave: Nay some, unmindful of themselves, as though they could not, or would not survive their beloved prince, it is reported…suddenly fell down dead."(2) I would like to add that there exists a tremendously aesthetic account of the many troubled tortures that members of our good society persevere through, as accounted in William Hogarth’s series of woodcuts Stages of Cruelty. As an aesthetician, these portrayals of societal drudgery are will demand anyone to seriously contemplate criminals and the justice system of England. Prosecution At this point, I have no further questions, and I would like to introduce the entire Stages of Cruelty , commissioned in 1751, by popular English artist, William Hogarth, as the first exhibit of this part of the trial.

The Prosecution has no further questions.

Defense Oh, how the Prosecution misunderstands the work of Hogarth! Viewing a small portion of his work reveals that Hogarth was certainly a man of his times, "he believed that the lived in a period of unprecedented lawlessness and that the only possible response was a policy of ‘ maximum severity.’"(3) It is difficult to enter the mind of the criminal. I will not attempt to reduce this humble audience to the cold-blooded mentality of criminals. Of course, it is quite simply for the prosecution, and David Hume, to stand before us and claim the dignity of human life without recognizing the harm that these social parasites inflict upon the population as a whole. As Leon Radzinowicz points out in his massive History of English Criminal Law, "replacing capital punishment with imprisonment was often replacing a quick and relatively painless death with a slow, torturous one, given the conditions of imprisonment."(4) We also must not forget the secondary importance of any punishment, which is to instill in the minds of others the chilling affects of crime, with some hope to deter future criminals from committing any crimes. Often we must use one criminal as an example for the benefit of the entire society at large; we must use this delicate balance of criminal’s rights versus societal health, functionality, and well being. Perhaps of the greatest importance in the oversight of the Prosecution not to take into account the common view of public executions. Over the past two hundred years, a great deal has changed, including the way death is upheld by Western society. Modern citizens living in so-called industrialized nations are divorced from the death and disease that permeated everyday life in eighteenth-century England. For centuries, public executions in England were one of the most popular forms of entertainment.(5) Compelling descriptions of these public "events" about in the literature and art of the day, detailing the "immense crowds of rich and poor alike jostling to obtain the best view-point, their mood varying according to their sympathies with the criminal."(6) Public executions were historically viewed as another way in which many diverse people could congregate harmoniously, such as taking a stroll along the Tames. Certainly, you can’t condemn an entire society for that! Public executions were not isolated events of random violence, they had a great deal of structure and organization. In Dorchester, the Maumbury Rings had been used at a public execution site for centuries. Dating back to Neolithic times, the Maumbury Rings was an arena with "tiers of seats on all sides [which] provided everyone with a good view and allowed a large crowd to be kept under control. It was used as a place of public execution until 1767.(7) It is the position of the eighteenth and twentieth century defense that capital punishment maintains stricter regulation and incorporate stricter policy, yet maintain itself as a viable method through which criminals are punished. At this point, I would like to call upon the very man who stood opposed to the execution of Reverend William Dodd. I call my witness, Samuel Johnson, to the bench. [Johnson takes oath and seats himself in the witness box] Defense Mr. Johnson, what is your stance on the elimination of the death penalty? Johnson I am a steadfast proponent of the sharp restriction of the death penalty, but I do believe that the death penalty should not be eliminated. (8) I believe, as I have written in Rambler 114, "that restrictions on the use of capital punishment would bring about more reasonable relationships between the crimes committed and the penalties imposed, and that would in turn bring about an improvement in the system of justice." In addition, my convictions dictate that until "we mitigate the penalties for mere violations of property, information will always be hated, and prosecution dreaded. The heart of a good man cannot but recoil at the thought of punishing a slight injury with death."(9) Defense So, you would not be opposed to the public execution of a vile and loathsome criminal? Johnson If regulations are established whereby it can be determined that certain set crimes result in specific and set punishments, then I see no reason why we should not punish the punishable. [The lead prosecutor boldly leaps out of her seat and delivers an impassioned impromptu speech] Prosecution Your Honour, I firmly object to the nature of this discourse. We are not here to debate the merits of capital punishment per se, we are here to determine the political, social, and ethical merit of executions made in public. While I remain firm in my belief of the heinous and unacceptable nature of capital punishment in general, this trial extends beyond the issue to include the witnessing of such executions by the masses. In the twentieth century, such an atrocity would simply not be tolerated, the more humane and philanthropic nature of our society becomes apparent in the public execution juxtaposition. Moreover, the prosecution is simply not taking into account the fact that while eighteenth-century English morality did not stand in opposition to public execution, at the dawning of the Victorian Age, the "era of public executions has run its course."(10) The spectacle of executions could not longer be justified, deeming August 10, 1858 at the date of the last public execution in England.(11) |