Introduction

The Sahel, a region between the Sahara Desert and sub-Saharan Africa, is one of the most naturally arid places in the world. Habitation has always been a struggle because the people of the Sahel have been constantly challenged by series of droughts and land degradation. Due to the harsh environment, there has been an intensification of conflict over natural resources. This conflict has displaced many people, such as herders and poor farmers, from their homeland or territory. Displacement has caused homelessness, loss of livelihood, and cultural dislocation. Such a situation has lead to the questioning of whether the ecological and social carrying capacity has been surpassed. Can droughts and land degradation ever be combated in this region to prevent further displacement? In order to answer this question, it is essential to understand the relationship between environmental change and population activities.

In this paper, the state of the Sahelian region and the reasons behind displacement and conflict will be analyzed through four different aspects that make up a "family of transitions." The first goal will be to assess the environmental situation of the region by understanding the reasons for desertification. I will demonstrate the ecological patterns and changes in this region, and how they relate to growing aridity. Although natural environmental alterations are an important aspect, I will primarily demonstrate the correlation between the population growth rate of this region and its environmental state. Within the umbrella of the population transition, I will also include the effects of population pressure that lead to the third transition, urbanization. The fourth transition that I would like to focus on is that of the economic changes. I will explore the reasons behind certain economic policies implemented by the governments of this region and the effect of the market economy on the rural sector. Finally, the last transition I will focus on is that of social change, especially in the lives of the herders. During the analysis, it is important to keep in mind that these transitions do not necessarily occur independently of one another. They are permeable and interconnected. Furthermore, it is essential to note that the Sahel is not a homogenous region. Each country is unique in terms of their environment, policy practices, and culture. It is only the overarching problem of desertification and displacement that is common in the five western Sahelian countries of Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Senegal that I will be concentrating on.

The four transitions that I have chosen to examine are all in a "vulnerable" state. Vulnerability, which mainly occurs in the early stages of transition, is determined when "rates of change are high, social adaptive capacity is limited…and the relationships in the dynamic are imbalanced" (Drake 1993: 303). It is the "vulnerability" occurring within environmental, population, urban, economic, and social transitions that are causing displacement and conflict between herders and cultivators. Although the Sahel is at a "vulnerable" state, there are policies that can be implemented to create a better future. However, first of all, it is essential to establish the environmental state of the Sahel.

The Environmental Transition

The Sahel is 500-1,000 km wide and stretches for 7,000 km from the west to the east coast of Africa. In the distant past, the Sahel was a "well-watered savanna" where forests, rivers, and grassland plains use to thrive. However, since 2000 BC the region has been drying up. The Sahel now mostly consists of a semi-arid ecosystem that fluctuates between grassland and shrubland thicket, where the rainfall is only between 150-600 mm/year. There are four different ecological zones in the Sahel: the sub-desert margin mainly located in Niger is sensitive to wind erosion since it is barely covered by vegetation; Sudano-Sahelian zone which falls in Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal has an annual rainfall between 350-650 mm; edapho-climatic zone in Burkina Faso which contains very poor soil quality and is susceptible to extreme climatic events; and the humid zone in Niger and Senegal which is affected by salinity and seasonal floods (Raynaut 1997: 31-35). Considering such a variety in terms of harsh climatic and ecosystemic zones, what have been the reasons for climatic change and degradation of the ecosystem?

One of the main causes of climatic change has been series of droughts that have affected this region. In this century, there have been at least six recorded droughts. One of these droughts recorded between 1968 and 1973, was declared an international disaster because rains failed for six consecutive years (Bennett 1991: 13). Droughts could be caused by several reasons. One reason could be the temperature change in the Atlantic Ocean changing patterns of rainfall in West Africa. Another reason might be the greenhouse effect in relation to the global concentration of greenhouse gases (Hume 1993: 44). In addition to droughts, desertification has also contributed to environmental degradation.

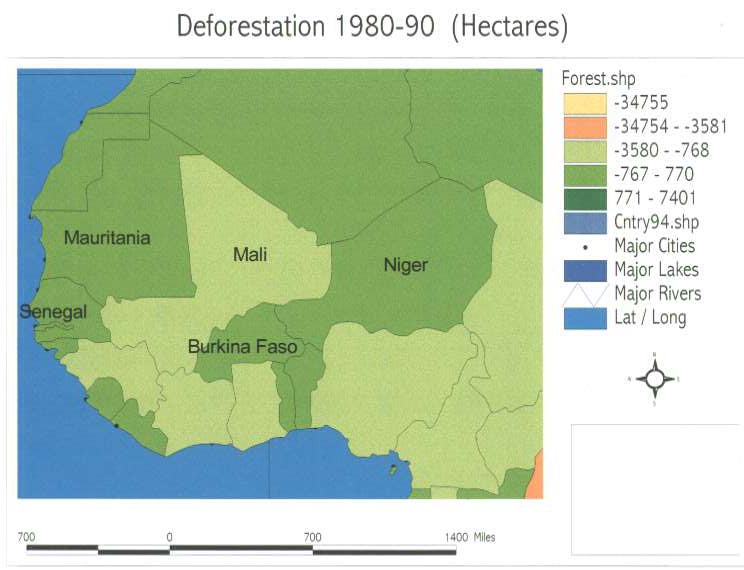

Desertification is growing at a very fast pace. Although it is understandable

that deforestation is occurring for commercial and subsistence usage, there

has been no encouragement for reforestation. Reforestation as a policy

should be enforced because it is crucial for maintaining a viable ecosystem.

| Mauritania | Senegal | Burkina Faso | Mali | Niger | |

| Deforestation

(1,000 ha/year) 1980-89 |

13 | 50 | 80 | 36 | 67 |

| Reforestation (1,000 ha/year) 1980-89 | (.) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

However, it is important to keep in mind that the popular image of the desert "spreading like a plague" is inaccurate. Instead, "the spread of the desert is more like a bad skin disease…individual patches then join together, until eventually a whole area is affected" (Bennett 1991: 14). Nevertheless, desertification is also caused by the increase of population growth. In order for people to feed a growing population, land use has been extensive in terms of, repeated cropping, salinisation, and land encroachment (IUCN 1986: 21). This has lead the land to be vulnerable to the loss of top soil and subjected to "nutrient mining."

The Population Transition

The population growth rate in Africa is considered "over-exponential." It has been predicted that by the year 2020, Africa will have 20% of the world’s population compared to the 12% it has now (Raynault 1997: 37). In the Sahel, there are 38.6 million people and the population is growing at an average rate of 2.88% (Human Development Report 1995: 179).

Figure 1; Actual data till 1994; Source: World Resources Institute (WRD)

By looking at Figure 1, it may seem as if population is decreasing.

However, it is important to notice the time lag between birth and death

rates (Figure 2). The average crude birth rate for the Sahel is 46.5 compared

to the 17.22 as the death rate (Human Development Report 1995: 179). The

birth rate is still greater than the death rate suggesting that the Sahel

is still in the early stages of the population transition. The Sahel is

clearly an example of a neo-Malthusian prediction where overpopulation

and this will lead to land fragmentation, over utilization of land and

a degraded environment (Mobugunje 1995: 6). Because fertility is almost

three times greater than mortality, population still increases at an exponential

rate. This makes the Sahel "vulnerable" in terms of the environment being

incapable of supporting more population growth.

Figure 2; Actual data till 1994; Source WRD

click here to see country-wise population projections

The "vulnerability" allows us to induce that there is an imbalance between the timing of environmental transition and that of population growth. What is important to note is the extent of vulnerability. So far, the analysis has been based on exponential projection. However, looking at the linear and especially the logarithmic projections on Chart 1, the extent of vulnerability is not as great as the exponential projection. Therefore, it could be debated that the Sahel should not be alarmed about the depletion of its natural resources or the neo-Malthusian predicament. Instead, sustainability or even entering the middle stage of the demographic transition, where births and deaths are coming close to bring equal, is closer than expected. This could imply that the Sahel is not at a fully "vulnerable" state. However, it is still important to keep in mind that at the present, all of these projections to some extent, demonstrate an increase in population and is susceptible to "vulnerability." The extent of "vulnerability" may differ in the future but it is the high probability of vulnerability now that we should be cautious of when making policies.

Even though the connection between population and environment can be debatable, there is evidence that there is a need to be weary. The increase in the mouths to feed, which is leading to the depletion of natural resources, will have future repercussions in terms of decreasing food production. As Figure 3 shows, with the exception of Burkina Faso, food production is already considerably fall. This could have detrimental affects on the health of the population. Therefore, not only is the ecological carrying capacity at stake now, but it will be in a worse condition by the year 2020 at the current rate of population growth when population will double (Human Development Report 1995: 79). This is a situation of positive feedback where an increase in population results in increase in environmental degradation. This positive feedback can be slowed down by through family planning measures within the societies of the Sahel as well as education. Population policies must also take into account geographical location of population density.

Figure 3; Source: WRD

The distribution of population in the Sahel is "discontinuous." In other words, in some areas, the population density is large and in others, hardly anyone inhabits the area. The most crucial indication of population density and carrying capacity is the climatic zones. With the worsening climatic conditions in the last twenty years and land degradation due to population growth, there has been a considerable amount of demographic decline in the northern areas. More people have been immigrating to the south because of higher precipitation and land fertility (Raynaut 1997: 47). In addition too natural population growth, migration to the urban southern areas is mainly responsible for conflict over fertile lands.

Urbanization Transition

Throughout history, internal migration has always occurred in the Sahel. Capital cities are especially "centers of attraction" because of employment opportunities. On the one hand, internal migration has created a considerable loss of population in the north and nation-wide, especially in the modern Sahel. For example, in Senegal, not only have people in the north immigrated to Dakar in the south, but many of those already living in Dakar have immigrated to Europe. Senegal represents a general trend in the Sahel. However, urbanization is not as prevalent in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger as it is in Senegal and Mauritania. In Mauritania alone, the rate of urbanization is 42%, a very high rate for most developing countries (Raynaut 1997: 75). Nevertheless, these "centers of attraction" have created an immense growth in urbanization.

There are four zones of urbanization in the Sahel. The first is in the

extreme west of the Sahel, which is characterized by "an area of urban

polarization." This area is very fertile and densely populated. The second

region is the Upper Senegal Basin where labor is exported to other coastal

countries, Bamako, or to Europe. The third region is between the Niger

River and western Burkina Faso. This area has a high population mobility

due to the search for favorable levels of rainfall. The last region is

located in the Nigero-Nigerian border. Although this region acts as "pole

of attraction," it shows no sign of "saturation" yet (Raynaut 1997: 85).

It has been predicted that "spatial

Figure 4; Actual data till 1994; Source: WRD

Distribution of population…will depend primarily on the balance established between two opposing forces: on the one hand, the capacity of rural regions to retain their inhabitants, and, on the other hand, the level of attraction exercised by the urban world." (Raynaut 1997: 83).

The rate at which urbanization is occurring suggests that there is an imbalance in the population flow between the urban and the rural areas. The imbalance is based on the timing of environmental and population transitions. The people of the north are vulnerable not only because of the high rate of environmental deterioration and population growth, but also because of dislocation. Dislocation is mainly occurring among herders being pushed into "foreign territory," threatening their traditional mode of livelihood and cultural life. Furthermore, the urbanization transition also jeopardizes the standard of living for those who were already settled in the "center of attraction." Playing more attention to the needs of the rural sector can dim the intensification of urbanization. For example, if reforestation took place, more people in the rural areas would have access to natural resources and they would not be forced to go to urban areas where the situation may be worse. Because such measures are not taken into account, regional conflict exists within the Sahel between herders immigrating from the north and cultivators in the south. The rate at which urbanization is occurring creates a scramble for the limited natural resources and is accentuated by the environment and population dynamics already in play.

The Herders’ Plight

Over half of the 40 million "livestock dependent" people in the world live in Africa (IUCN 1986: 28). Herding in the Sahel has been a very important way of surviving for centuries, especially in the northern parts of the region. Pastoralists are known as the "Bedouins" made up of ethnic groups such as the Moors, Tuareg, and Toubou. In the past, there was a great balance between the number of herds, herders, cultivators, and the ecosystem. For example, the animals would convert sparse vegetation into milk and meat while providing manure for farmers (Bennett 1991: 18). Among many ethnic groups in the Sahel, such as the Fulani in Mauritania, cattle are considered a form of wealth. Meat is not consumed but traded for agricultural products. If tension between herders and cultivators was minimal, what then set off the trigger between these two groups of people?

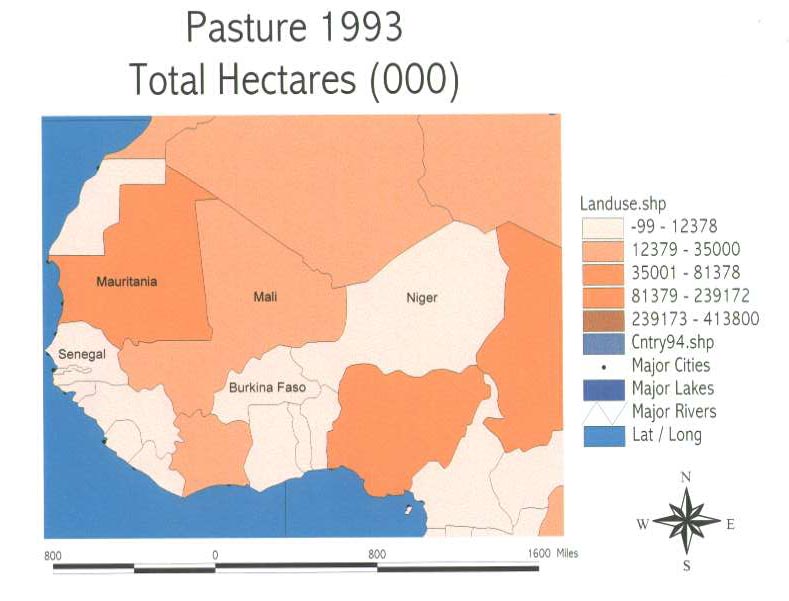

One answer is again the issue of drought, which reduces the resources for humans and livestock. The search for fertile land, especially in times of droughts, leads to permanent land degradation. This forces pastoralists to roam within smaller or marginal areas leading to overgrazing, preventing future regeneration of vegetation, and a significantly reducing productivity of the pasture. The primary erosion loop is the erosion of grass. When the grass is eaten down by the herds there is less vegetation, lower topsoil, and moisture, making erosion permanent (Meadows 1992: 128). Ironically, the drilling of more wells in order to ensure that there is at least some availability of water during droughts and the dry seasons, have also lead to more over-exploitation of land by the herders. The increase of livestock and wells, "blur the map of social control over the pasture lands" (Raynault 1997: 123). Wells create their own "center of attraction" while degrading land that they are on. Additionally, it is also the increase of livestock that eliminate fertile land in addition to human resource use, leading people and their cattle to the south.

| Total Number of Cattle (1,000) | Mali | Mauritania | Niger | Senegal | Burkina Faso |

| 1990 | 4996 | 1350 | 1711 | 2740 | 3937 |

| 1991 | 5198 | 1400 | 1790 | 2770 | 4015 |

| 1992 | 5373 | 1400 | 1800 | 2800 | 4096 |

In the south, herders are threatened by the growth of agricultural land and land privatization. Many governments in this region since independence have implemented private property laws. This automatically becomes problematic for nomadic herders because they do not believe in "artificial borders." The prejudice, especially against nomadic pastoralists, has been in existence since the colonial days where the goal was to have better control over people to secure taxes from populations with "unused wealth." More specifically, since the 1990’s the Taureg, a nomadic pastoral ethnic group in this region, have suffered rebel attracts by cultivators and air raids by the Nigerian government because they refuse to pay taxes. This conflict has spread to the Malian borders (Bennett 1991: 53-56). This example illustrates that there is no "rational" contact between the governments and nomadic populations, such as the Taureg. Not only do the people like the Taureg have little participation in the decision-making processes of the country, but the only form of contact comes through tax collection. The contact between pastoralists at the grassroots and administrative levels are as if it is through "the republican guard, who mostly behave as if they were on conquered territory, and because of this they [herders] symbolize pure violence in the eyes of the population (Bennett 1991: 57). The governments fail to recognize the limits of the environment, and the population transitions of the humans and the herds. This, thereby, marginalizes and further displaces herders. The governments’ place more emphasis on cultivation.

Agriculture

The other component of this vicious cycle is the extensification of

agriculture. For instance, since 1985 in Senegal, the implementation of

"structural adjustment" policies and cash cropping has increased the quantity

of farmers who arbitrarily clear land in order to be coerced into the greater

national economy. Once the land has been used, farmers move on to more

cultivable land. This practice not only hurts herders who may come to the

same piece of land for their animals to graze only find it infertile, but

it is only based on short term gains (Bennett 1991: 42). This is mainly

the case because most of the farming in this region is extensive and based

on shifting cultivation. Slash and burn methods are also used where lands

lay fallow, reducing the amount of land available for use. When land is

in short supply, the fallow period is shortened and the land no longer

has sufficient amount of time to regain its production capabilities.

Arable land is increasing majority of the areas because a greater emphasis is placed on agriculture.

Figure 5; See map on cropland for more data; Source: WRD

Nutrient mining pushes both farmers and herders to more fragile areas. Although cultivators may seem to be in a better position than herders, especially by having government support and property, there is a great disparity between rich and poor farmers. The social vulnerability between herders and farmers and among farmers themselves can be explained through the economic transitions.

The Transitions to Market Economy and Government Intervention

In conjunction with environmental and population transitions is the economic transition. The market economy and integration of agriculture into national economies influence economic transition. After independence, the goal for these Sahelian countries was not only to become "developed" but also to finance growing foreign debts. The only way to fulfill these objectives is to rely on agriculture. Agricultural production can not only feed the nationals of a country, but can also be used as export crops to receive hard currency for further development and financing debts. Governments support agriculture for sustained economic growth because it is lucrative and has the potential to alleviate poverty. Unfortunately, these theories about agriculture were not implemented efficiently. International donor agencies such as the World Bank advocated structural adjustment policies where aid would be tied to economic stabilization. Structural adjustment policies were also highly coercive. In order to receive aid, a country had to engage in privatization and liberalization of its economy. This is not necessarily a negative policy but it has been enforced without understanding the socio-economic situation already in existence in the Sahel. Such a policy failed to take into account the costs of privatization among herders, and especially, poor farmers. This negligence has caused serious environmental deterioration and conflict.

Privatization of land through the market economy is a new phenomenon that has resulted in inequality financial as well as access to land (Raynaut 1997: 258). Traditional land entitlements laws still exists but has been nullified to a great extent with establishment of nation states. The extent of nullification varies from state to state - in Niger land belongs to those who "develop" it and in Senegal, traditional land rules are nullified. Overall, access to land is determined by who has more financial resources. Not only does this exclude herders and poor farmers who lack finances, but it is completely foreign for herders. Such a situation gives the rich farmers the option to use land unsustainably by buying more and more land without any concern for future repercussions. Additionally, due to the lack of "economic assets," the poor have no rights. They also do not have any access to credit they need to invest in the new technologies or infrastructure (Mobuguje 1995: 32). Because of this, they too encroach on marginal lands and making the future more vulnerable in terms of feeding a growing population.

The key to a successful future in the Sahel is to invest in agriculture because it has the potential of feeding more people and producing more money. However, it is not being practiced in a sustainable manner nor is the greater economy including herders in the process of economic growth and eradication of poverty. The concept of profit and the "get rich quick" phenomenon that results form privatization and liberation of the economy can lead to the "race for land" and conflict. This form of social and economic vulnerability can be reduced if governments advocate a more equality for both herders and poor farmers in terms of access to land or subsidize the poor farmers by providing them fertilizers, securing tenure rights, and educating them about soil conversation methods. In other words, emphasis must be placed on intensification of land use rather than extensification. Agricultural economists such as Ester Boserup states that population growth where "intensive agricultural practices…induce[s] more favorable attitudes toward technological and organizational innovation that will not only increase productivity, but improve environmental quality" (Mobagunje 1995: 6). It is then possible to redistribute the wealth from agriculture into other economic sectors such as herding to alleviate the herders’ level of poverty and create better sustainable grazing rights. In addition to redistribution of wealth, there can be a greater initiative placed on a "double strategy" where agricultural practices can be combined with herding. Like in the past, the increase of fertilizer use, for instance, can come from herding practices. For example, there are societies in the Sahel such as the Haalpulaar of the Senegal River where the results of cultivation and herding create a cyclical pattern. In this "double strategy," the residues of the flood plain agriculture create a common grazing land, the excrement from herds provide nutrition for the fish, and the organic waste helps produce more vegetation (Raynaut 1997: 115). However, with the current means of economic growth, social conditions are "vulnerable" leading to more hardships.

Social Dimensions of the Sahel

Such traditional methods of social and land control systems are now under serious threat from both the agriculturist and pastoral perspectives. The economic transition and the introduction of the use of money can explain the social transition. The process of integrating the local economy or those living in the rural areas into the greater world economy has put an emphasis on individualization and monetary profit. This has caused disintegration of social structures such as the family. For instance, young people and women are now investing in their own plot of land. Ironically, to a great extent, the disintegration of the lineage and family structure is reducing economic productivity because small, individual production units are unable to mobilize work force at crucial times (Raynaut 1997: 280). If family units become smaller, they may fall behind in sowing or weeding, resulting in lower productivity and extensification. The loss of one family member, especially in agricultural societies, is greatly felt because it affects future population sustainability (Raynault 1997: 280). Additionally, those who migrate to the urban areas also pose vulnerability as family ties become disconnected. The migration for profit (although essential) can lead to anomie or alienation from the new atmosphere resulting in cultural deterioration. However, it is important to note that such reasoning is not advocating that people should remain in one place just to prevent social disruption while going hungry. The evidence of social vulnerability should be used as a sign that a significant portion of the policies made in the Sahel should emphasize the need to improve rural areas. If reforestation and better infrastructure were provided as an incentive to stay in rural areas, then social or familial disruption would be minimized.

click here for a "theoretical diagram"

Policy Proposals and Conclusion

Governments need to invest more in the rural areas and place less emphasis on maintaining the political support of urban populations, especially the civil servants, army, and the police (Grainger 1982: 61). Although urban needs are no less important, majority of the population in the Sahelian countries still live in the rural areas where effort to encourage sustainable growth should be emphasized. Initiatives should be taken to increase reforestation as a direct solution to desertification. Reforestation as a policy also has the potential to decrease the rate of urbanization and perhaps social deterioration. Maintaining a sustainable ecosystem can also come with an early population stabilization no matter what projection is used. Reducing population, through education and family planning can significantly reduce the detrimental effects on the environment (Meadows 1992: 29). However, it is important to keep in mind that population pressure is not necessarily a problem. Taking into consideration Boserup’s theory on the increase of agricultural production through intensification of land use, population can be "put to work." Boserup’s theory has been practiced in Machakos, Kenya and it could work for the Sahel as well. The conditions in this region improved due to initial accumulation of capital and skill (Tiffen 1994). The accumulation of capital could lead to communal investment in other sectors of the economy, alleviating poverty and improving the state of the environment. The initial capital could come from investing in agriculture.

Investing in agriculture will not only be able to feed the growing number of people, but it will also help the Sahelian governments finance foreign debts. However, agriculture will only be beneficial if it is practiced sustainably and equitably through better access to land and infrastructure. Herding communities will also be able to receive benefits through redistribution of wealth. It is evident that the importance of herding is decreasing because it is not as lucrative and is a livelihood much harder to monitor due to its nomadic nature when considering integration into the world economy. Nevertheless, it is crucial for governments of the Sahel to integrate herders, a significant part of the population, into development. If all of these policies just suggested are practiced effectively, the Sahel should see fewer tensions between herders and farmers over scarce resources.

All the transitions presented in this paper have positive feedback loops where the increase in environmental degradation increases population vulnerability and urbanization. The current haphazard economic transition, increases inequality and social vulnerability. Because the conglomeration of these four transitions that are out of sync with each other, they foretell the future of overshoot and collapse. With the data and the analysis provided, it is highly likely that the carrying capacity of the Sahel will collapse because the "signal from the limit is delayed" and the environment is "overstressed" (Meadows 1992: 128). The rate at which the population is growing, the environment is being used, the economic and social pressures are forcing people to use the land extensively, will lead to the collapse of the resource base leading to an ever-present state of vulnerability. Interpreting these signals correctly and making policies for long-term sustainability is essential in order for the Sahelian people to live sustainably and without violence.

Bibliography