|

Anson Brown was a fairly wealthy land

owner. His properties were north of the Huron River in a

region called Lower

Town. Brown was constantly

competing with the people of the downtown area which he

referred to as "the hilltoppers." Lower Town was not in the

original plat of Ann Arbor, so it was technically a separate

village. Brown had a vision to make Lower Town just as

prosperous as "the hill," but he had trouble getting

settlers to move to Lower Town despite the fact that the

land was considerably cheaper there. One important reason

for his difficulty was the mail. Mail came from Detroit and

was delivered in Ann Arbor. Consequently, people wanted to

live near Ann Arbor. Later, a post office was to be built and Brown persuaded officials to build it in

Lower Town. This was quite a victory,

and population

started to increase in the area.

Soon, a railroad was to be built there as well.

|

|

|

|

James Kingsley was the first attorney of Ann Arbor and a

well-respected citizen. In 1828, he was elected judge of the

probate court. In 1837, he was in the Lower House of the

State Legislator and eventually State Senator. Most

importantly, Kingsley was always devoted to Ann Arbor, and

was instrumental in bringing education to the forefront of

the community as a regent of the University of Michigan.

Initially, education was difficult for the settlers. Schools

would be founded, but the average life span of these

institutions was about two years as most citizens could not

afford to send their children to these schools.

|

|

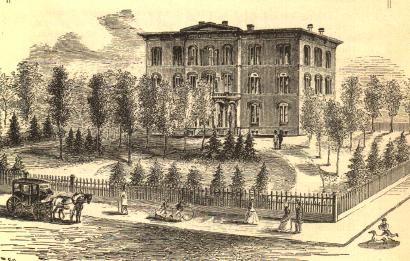

The village council began building public schools, and

later built one of the costliest buildings in the state, the

Union School, later renamed Ann Arbor High.

|

|

The single most important event in Ann Arbor's history,

and what will forever intertwine the city with education,

occurred in 1837 when Ann Arbor was chosen as the new site

of the state university. The price for such an honor was

forty acres of land the village council was more than

willing to give. The State Journal wrote: "Our village, we

trust, is destined to be the pride and ornament of Michigan"

.

|

|

The addition of the University of Michigan to Ann Arbor

changed how the city operated. The people of the city began to take

pride in the university and in Ann Arbor as a place for scholars.

However, they did not want certain aspects of university life

affecting their community. To combat drunken students╣ presence in

the streets, for example, ordinances were passed prohibiting the sale

of alcohol to students. There was also an ordinance prohibiting

saloons from operating on Sundays. The town felt they had a great

interest in the university because the university affected their

livelihood, such as housing and trade. "That in the prosperity of the

university depends, in a great degree, the prosperity of our village;

and hence it is not only our right but our duty to look to the manner

in which its affairs are managed" (Michigan Argus).

|

|

|

|

A glorious day came when in 1851 George Sedgwick brought

news that Ann Arbor had officially become a city. Great celebration

followed as the townspeople were so happy, and Sedgwick became

the first mayor of Ann Arbor.

|